Traditional models being used to address longevity and sequencing risk in retirement lack reliability, but a new method may be able to provide greater certainty around planning for this life stage, says Melanie Dunn.

One of the most commonly stated concerns of retirees is outliving their retirement savings. This is understandable because living off savings for an unknown time frame is a very different challenge to living on a regular salary.

Retirees can take one of a number of different approaches when living off their retirement savings:

- excessive caution, for example, living only on their income,

- wishful thinking, for example, continuing pre-retirement spending habits and hoping things will work out okay, and

- careful management, for example, proactively managing retirement risks, accurately budgeting planned expenditure and maximising any age pension entitlements.

In an SMSF, the individual retiree is generally responsible for all decisions around investment, inflation and longevity risks. In order to be confident of not outliving their retirement savings, each household must maintain a buffer for their own risks. But how exactly should they do that?

This article will examine how the thinking and techniques that actuaries use can apply to individual retirees and households in retirement.

The SMSF investment strategy requirements

Section 52(2)(f) of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) (SIS) Act and regulation 4.09 of the SIS Regulations require SMSF trustees to “formulate, review regularly and give effect to an investment strategy that has regard to the whole of the circumstances of the entity”.

In order to meet the requirements of the legislation, the trustee and their advisers must have an understanding of the members’ objectives and cash-flow requirements. Objectives include such things as the members’ desired annual budget, of which drawdown from the SMSF may be a key component, and any amount they wish to leave their children or others.

Determination of an SMSF’s ability to meet such objectives requires consideration of the most likely outcome and also the range of outcomes based on their chosen investment mix.

The trustee should ideally be making an informed decision based on the range of outcomes they’re willing to accept. If they are not comfortable with the range of outcomes, then they might need to reassess the fund’s investment strategy or the objectives.

How to model retirement

Retirement modelling is very complex. In order to assess the sustainability of a retiree’s assets against a desired spending pattern, a robust model must consider many overlapping factors such as:

- the ages of household members, which usually differ,

- non-superannuation wealth,

- investment mix or asset allocation both inside and outside super,

- the taxation treatment of income and assets,

- any entitlement to the means-tested age pension that can vary over time as capital is consumed,

- investment returns on each asset class held net of fees, and

- household spending patterns that will change over time and be affected by inflation.

Common approaches to retirement modelling recognise these factors, but often make large simplifications and assumptions against them. These deterministic models consider a single scenario and use a set of constant fixed assumptions, which are assumed to be achieved in every year of the forecast.

Deterministic models are easier to develop, but have limited utility because they say nothing about the range of outcomes the retiree will face. Many such models also fail to take into account important factors like differing asset allocations and sequencing risk with volatile assets.

In many ways, deterministic models can’t be relied upon and risk disappointing retirees who heed their outputs. This is not an acceptable situation given retirees are faced with extremely important decisions about their chosen spending level in retirement. It is important to ensure the tools they use are robust, holistic and take into account the uncertainties they face.

A holistic model of retirement will consider each of the three key risks – investment risk, inflation risk and longevity risk – and also take into consideration all of the above bullet points.

We will now focus on the key considerations around investment risk in particular.

Investment risks in drawdown phase

When setting up an investment strategy to deliver specific objectives, choosing a risk/return position can be a difficult trade-off. It is vital to consider how much capital is exposed to investment markets and for how long it is likely to be invested.

The fact this capital may be required to produce retirement income for 20 or 30 years, or more, makes it tempting to invest in assets with higher historical average returns.

However, the mathematics of portfolios in decumulation make the risk of failure higher for SMSF portfolios in pension phase. Because retirees’ assets are being drawn down, the ability to recover from negative returns is reduced and so the timing of market downturns can have a significant impact on the sustainability of the assets.

A deterministic model assumes a constant fixed return is achieved every year and does not allow for the chance of market crashes nor illustrate the range of returns a household’s investments might experience. This can lead to a false sense of security in the investment allocation.

Indeed, the notion of average returns can be highly misleading, especially when looking at volatile asset classes. Indeed, the average return may never actually be received in any given year.

It’s the actual experience and sequence of returns achieved by the member that is important in real life. Therefore, modelling the range of returns is critical when developing an investment strategy. The range of possible returns for any investment mix needs to be applied to the member’s personal situation in order to identify the range of possible outcomes for the member’s retirement.

Case study 1: Forecasting using fixed assumptions

Consider Jenny, a retiree who requires a series of cash flows that increase in line with inflation. Her particular circumstances are as follows:

- single female retiree, aged 65 (average health),

- wealth of $700,000 (all in an SMSF),

- draws $50,000 a year, linked to inflation, and

- ignoring social security benefits and tax.

A deterministic model would take an assumed investment return and inflation rate and forecast Jenny’s SMSF balance using these fixed assumptions.

For example, consider that each year Jenny’s investments are assumed to grow by 8 per cent less her drawings, which are assumed to increase by an inflation rate of 3 per cent annually.

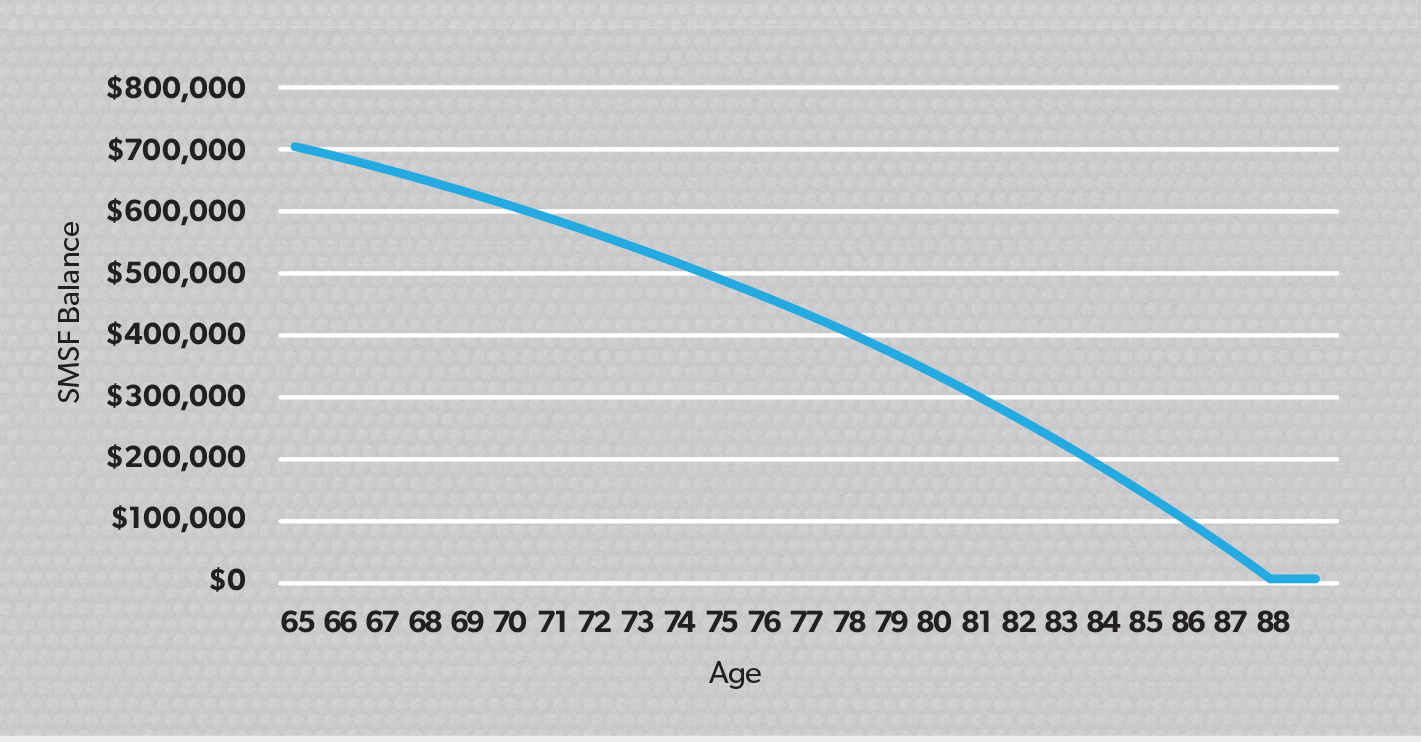

Figure 1 shows the forecast of Jenny’s SMSF balance in today’s purchasing power. Future inflation has been removed from the figures. Based on these assumptions, Jenny could maintain her desired lifestyle until the age of 88.

Figure 1: SMSF balance forecast (Spending $50,000 pa increasing in line with inflation

Figure 1 above is effectively ignoring risk. It is showing one possible, albeit extremely unlikely, outcome the SMSF might experience.

Jenny may be comfortable with the outcome predicted in this graph, however, it provides no information about the chance this scenario occurs in practice or the range of outcomes Jenny might experience.

Three key factors that will materially affect the outcome, being investment risk, inflation risk and the age pension, are not taken into consideration.

One way retirement models can start to incorporate risk is to use the pattern of historical returns. This shows the impact of returns that are different year to year.

Case study 2: Forecasting with an allowance for investment risk

Let’s again consider Jenny from case study 1 and look at what would have occurred to her SMSF balance had she experienced some actual historical returns. We assume here Jenny’s SMSF is invested in 40 per cent Australian shares, 5 per cent Australian bonds, 30 per cent cash and 25 per cent Australian listed property.

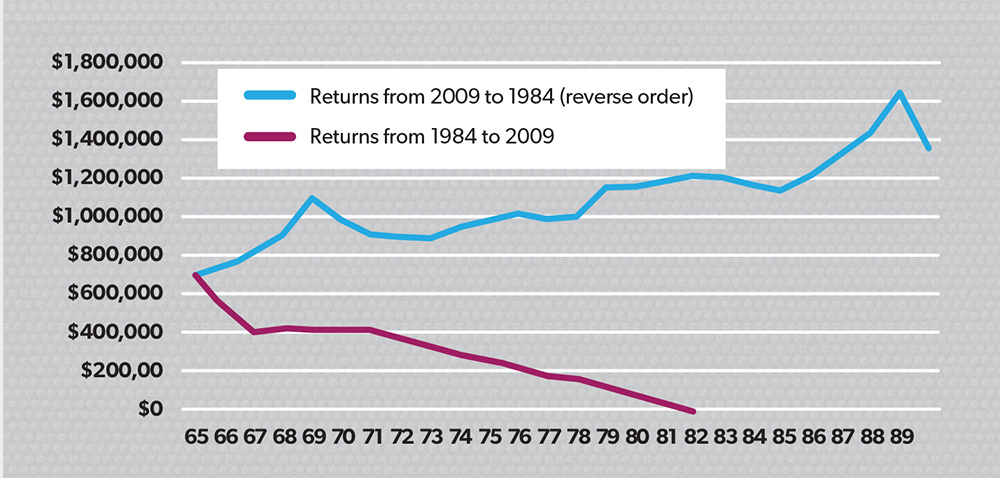

Figure 2, from Vanguard, shows a forecast of Jenny’s SMSF balance using the following periods:

- 1984 to 2009 – this was the best time frame for these cash flows, and

- 2009 to 1984 – to show what would have occurred if the best returns were experienced in the reverse sequence.

Figure 2: SMSF balance (Spending $50,000 pa increasing in line with inflation)

Using the best returns for this investment mix as achieved from 1984 to 2009, we can see Jenny’s assets increased in value despite her annual drawings. If these returns were experienced in reverse order, we would see the effect of some large negative returns occurring in the early years after retirement (those that occurred in 2008/09). This would significantly reduce Jenny’s assets and therefore reduce her capacity to fund her desired spend for the remainder of her retirement. She would run out of assets at the age of 82.

While both scenarios share the same long-term average return, their ability to produce sustainable retirement income varies dramatically.

This comparison of forecasts demonstrates the risk of using fixed assumptions. The pattern and timing of returns can have a very material impact on how long assets might last in retirement.

For SMSF trustees, and indeed any retiree, it is essential to explore the range of possible outcomes in order to assess the long-term sustainability of any spending plan.

Choosing a spending level

Case study 3: Matrix of affordable spending levels

Consider again our SMSF retiree Jenny. She is aged 65 and has $700,000 in assets in her SMSF. She wishes to spend an amount that increases each year with inflation and draw this amount from her SMSF.

Jenny’s life expectancy from age 65, allowing for standard improvements in life expectancy, is 89 (a further 24 years). As actuaries, we estimate she has a 25 per cent chance of surviving to 95 (a further 30 years), and a 10 per cent chance of surviving to 99 (a further 34 years).

The following levels of spending are sustainable based on various time horizon and fixed return assumptions, such as an inflation rate of 3 per cent and having spending patterns increase annually with inflation and paid uniformly:

Level of spend affordable with $700,000 in SMSF assets

Jenny is now faced with a complicated problem. She knows it is highly unlikely she will receive any of the fixed returns each and every year into the future and therefore the results do not allow for investment risk.

Jenny also knows it is highly unlikely any specified time horizon will be correct. Finally, she knows she is likely to receive entitlements from the age pension that will help to fund her spending, however, that has not been considered here.

This makes it extremely difficult for her to understand how confident she can be with any single scenario. In the table above, the resulting answer for how much she can spend each year varies from $28,000 a year to $49,000.

Jenny is faced with multiple layers of risk. How does she decide on a sensible level of spending? There is an answer, but it lies outside of the world of deterministic modelling.

Stochastic retirement modelling

Instead of projecting a single outcome, a stochastic model is one that explores the full range of possible outcomes that are capable of occurring. Commonly, hundreds or thousands of projections can be run, each one based on a different possible sequence of future returns and inflation the retiree might face. Each of these scenarios is called a simulation.

By carefully choosing a set of simulations that has a similar distribution to how real markets and inflation work in practice, we can run models that test a household’s retirement through a full range of likely outcomes.

This enables members to answer questions like: “If I retire today, how likely is it that my retirement capital will last me for life?”

To make informed decisions, retirees need robust real world models that can handle the complexity of Australia’s retirement system, make due allowance for the unknown, and provide retired Australians with the confidence they need around outliving their retirement savings.

By keeping an eye on the long term, professionals can add significant value by addressing retirees’ concerns and protecting the sustainability of their retirement lifestyle.