Re-contribution strategies can reduce the tax liability of an SMSF and its beneficiaries as well as allow members to qualify for Centrelink benefits. Karen Dezdjek illustrates how.

A re-contribution strategy for SMSFs is easy to implement. It has the potential to deliver significant tax savings to both the member and their beneficiaries when a member dies, not to mention potential access to Centrelink benefits they may have otherwise forgone.

So what exactly is it?

As its name suggests, a re-contribution strategy is where money is withdrawn out of the SMSF from a member’s entitlement and then deposited back, allocated to the same member or even the member’s spouse.

A member’s balance typically consists of two components – a taxable and tax-free component. A taxable component is derived from employer or member contributions where they have claimed a tax deduction. The tax-free component results from a contribution into the fund where no one is claiming the amount as a tax deduction. The idea behind the strategy is to convert a member’s balance that is predominantly taxable into a balance that is predominantly, or entirely, tax-free.

Sounds easy. So what’s the catch? In order to use this strategy a member will need to meet a condition of release to be able to access their benefits and then be in a position to re-contribute the money back into the fund either for themselves or their spouse.

What are the benefits?

Like most strategies the main aim is to save on tax. This strategy has potential benefits for anyone who has a taxable component and is able to access their entitlement.

Members up to age 60

Those who are under the age of 60, have permanently retired, have a high taxable component in their member balance and wish to begin a pension to have the ability to save some tax can benefit from the strategy. As we know, drawing a pension from the fund up until age 60 will mean there will be tax payable at the member’s marginal rate less the 15 per cent tax offset. However, if a condition of release, such as retirement, has been satisfied, a member can use their tax-free lifetime cap by withdrawing up to $195,000 (2015/16 rates) and then re-contribute this amount back into the fund as a non-concessional contribution. The non-concessional cap is currently set at $180,000 a year with the ability to bring forward an additional two years of non-concessional contributions. It is important a member checks they haven’t previously triggered the bring-forward provision before using this strategy, otherwise an excess contributions assessment will be issued.

Let us explore a practical example.

Case study

Jim is 57, retired and has a marginal tax rate of 32.5 per cent. He has $400,000 in his SMSF totally comprised of a taxable component and wishes to begin a pension.

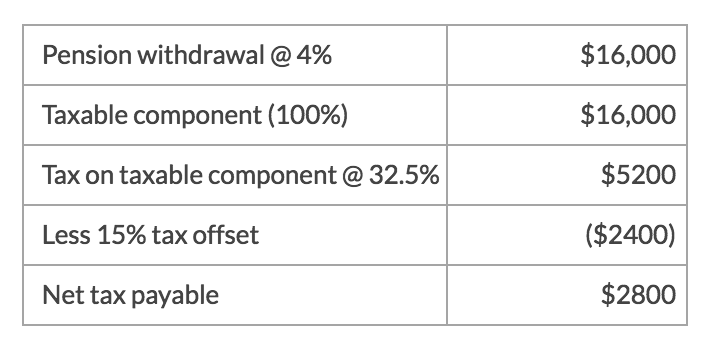

Assuming Jim begins a pension, his personal tax position would, by default (ignoring the Medicare levy), be:

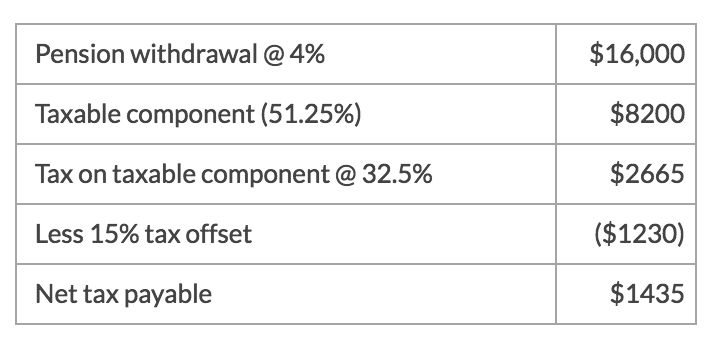

Alternatively, let us assume he fully uses his tax-free lifetime limit and withdraws $195,000 and re-contributes this amount as a non-concessional contribution:

The tax saving is $1365. While this may be considered small, the saving is compounded by the fact it will occur annually up until the age of 60. Over the next three years that is a minimum of $4095.

Members aged between 60 and 65

Many people are under the impression death taxes don’t exist in Australia. Unfortunately, there is a form of death taxes that are levied when non-dependants receive a death benefit that contains a taxable component. Members over 60 who anticipate there will be a benefit remaining after they die can potentially save their non-dependent beneficiaries (adult children) a significant amount of tax, ensuring the maximum entitlement possible is received.

Case study

Let us consider Jim again. He is now 60 and is looking to roll in his other superannuation entitlement he held via a fund with his employer. His fund over the years has done very well and his entitlement is worth $1.2 million and has a taxable component of $960,000 (80 per cent). His SMSF has also done well and is now worth $600,000, even though he has been withdrawing the minimum pension.

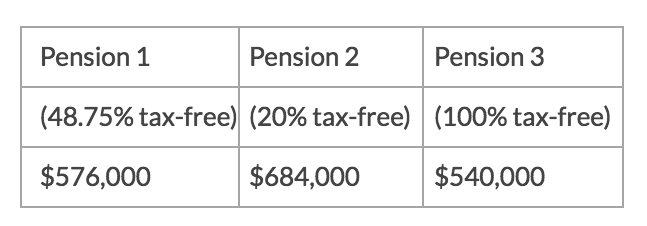

Jim lives a frugal lifestyle and doesn’t require anything further than the minimum repayment in order to live comfortably, and believes he will have a balance left when he dies to pass on to his adult children. At 60, he knows he is going to be able to trigger his bring-forward rule twice before he turns 65. He makes a decision to roll in the $1.2 million and then begin a second pension. He then withdraws the minimum 4 per cent from his original pension and withdraws from the second pension the remaining amount to take the combined withdrawal up to $540,000. The following day Jim re-contributes the $540,000 back into the fund and begins a third pension. His pensions now are:

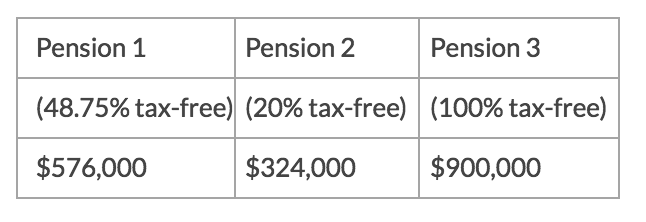

Jim continues over the next three years to take the minimum repayment, but with a little growth. The income the fund generates maintains the capital. His three years have now finished and he is in a position to withdraw and re-contribute again. It is better for him to withdraw only up to his single rate cap of $180,000 and re-contribute this amount. He will do this for the next two years. After the two years of withdrawing an additional $180,000 per year from pension 2 and re-contributing to combine with pension 3, his balances are (and for simplicity we are going to assume minimum pensions have been withdrawn from pensions 1 and 3, but capital has remained intact):

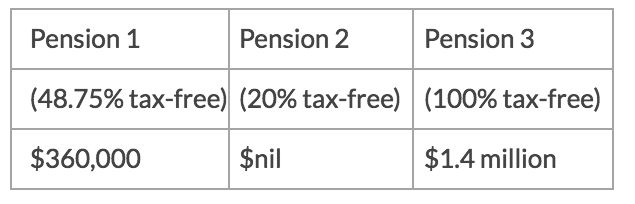

In the financial year Jim turns 65, he triggers his bring-forward rule and re-contributes $540,000 for the final time. He has the ability to withdraw the full $324,000 from pension 2 and also $216,000 from pension 1 and consolidate once again with pension 3. His balances now are:

Let’s assume that Jim, after completing this process, passes away. His adult son receives the full entitlement. As pension 3 contains a 100 per cent tax-free component, there will be no tax to pay on this amount. As pension 1 has a taxable component, he will need to pay tax on this amount.

Pension 1: $360,000

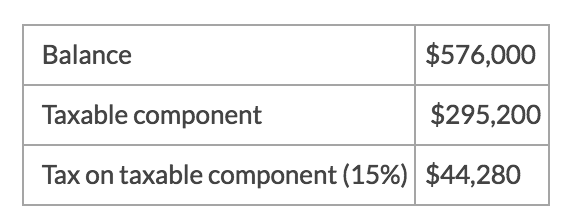

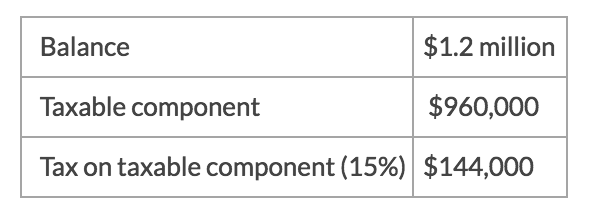

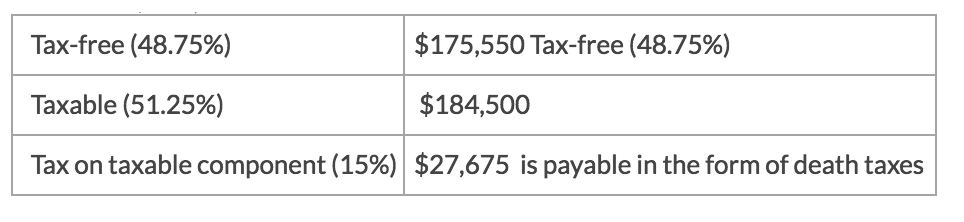

So what if Jim hadn’t entered into a re-contribution strategy after he initially went into pension mode? The death taxes would be as follows:

Pension 1 (48.75% tax-free)

Pension 2 (20% tax-free)

The death taxes payable if Jim did nothing total a massive $188,280.

While the above example of Jim has been simplified, it highlights the ability to save a huge amount in tax. The only question to answer here is who does Jim want to get his money – his son or the ATO? A no-brainer really.

Members aged 65 and over

Let’s consider another Jim who has a super balance of $850,000. He is married to Sally who is 61. Jim will turn 65 in six months and would like to be eligible to receive Centrelink entitlements. In his current situation he will not be entitled to any Centrelink benefits as he has too much in his own name. Jim decides to withdraw $540,000 from his superannuation entitlement as a pension and re-contribute this back into the fund in Sally’s name. Doing this will allow Jim’s superannuation entitlement to drop below the cap and he will be eligible to receive a part pension. The good news is that by contributing to Sally’s balance, and if she remains in accumulation mode, her entitlement is not counted by Centrelink. Jim and Sally will enjoy some form of Centrelink benefits for at least the next few years until Sally turns 65.Are there any disadvantages of using a re-contribution strategy?

While there are a number of advantages, like all strategies there are always a few points to consider. For a re-contribution strategy to work, a member must physically withdraw the cash from the fund. If the fund is heavily invested in assets such as shares, there may be a need to sell down assets and incur costs such as brokerage.

Some of the assets may be held in investments that take time to liquidate and therefore there is the opportunity cost of not being fully invested.

If a member is currently receiving an entitlement from Centrelink, the amount withdrawn may affect the member’s ability to continue to receive the entitlement in the short term. This could mean loss of the pension, as well as the valuable health benefits card that could prove quite disastrous financially.

Finally, if a re-contribution strategy is used, the fund will lose the ability to use the anti-detriment provisions. This should be considered if the entitlement is to go to a dependant, as they will lose the ability to claim an anti-detriment payment.