The First Home Super Saver Scheme is a mechanism that was handed down in the 2017 federal budget to help address the housing affordability problem for younger Australians. Rob Lavery examines how the scheme works and how effective a strategy it can be.

The 2017 federal budget included a suite of housing affordability proposals, the centrepiece of which was the First Home Super Saver Scheme (FHSSS). The scheme has since been passed as law and it provides the first tax-efficient mechanism by which first home buyers can save a deposit since the abolition of the much-maligned First Home Savings Accounts in 2015.

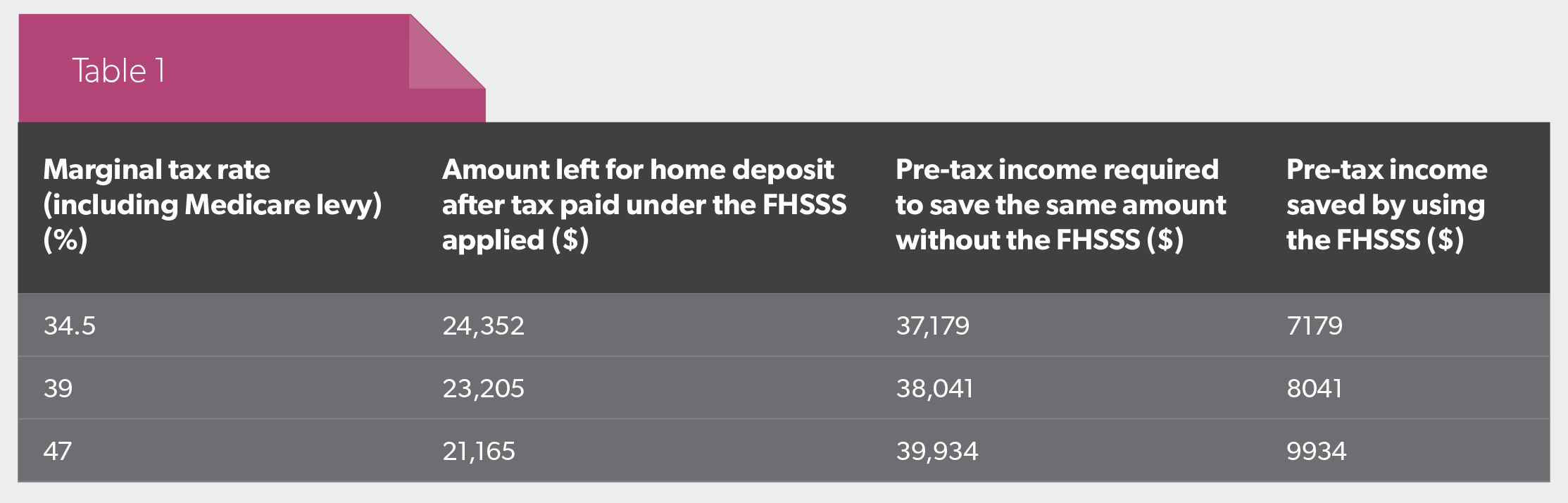

Unlike its ill-fated predecessor, the FHSSS facilitates potentially significant tax savings when compared to saving using post-tax income. Those in the top tax bracket can use almost $10,000 less in pre-tax income over two years to save the same amount and the savings are certainly not limited to the highest income earners.

How it works

In a nutshell, the FHSSS allows first home buyers to withdraw voluntary super contributions to purchase their first home. It will be administered by the ATO and contributions from 1 July 2017 are included in the scheme.

There are some basic eligibility criteria. The member needs to be 18 or older, have not owned an Australian property, nor had an amount released under the FHSSS previously. Unlike other first home buyer initiatives, a first home buyer can use the scheme even if they are jointly purchasing their first home with someone who has owned property before.

Contributions

For contributions to be accessible under the scheme, they must be voluntary, made by the member or their employer, and count towards the concessional or non-concessional contribution caps. In practice, this means deductible and non-deductible personal contributions, as well as salary sacrifice, can be withdrawn under the scheme.

Mandated employer contributions (including contributions that meet an employer’s superannuation guarantee obligations), capital gains tax cap contributions and government contributions (such as the co-contribution) cannot be accessed under the scheme.

The total contributions a member can withdraw under the scheme are limited to $15,000 a year, up to a lifetime maximum of $30,000. While the gross amount of any eligible contribution counts towards these caps, only 85 per cent of concessional contributions can be withdrawn. This allows contributions tax to be withheld.

Withdrawals

Withdrawals will be permitted from 1 July 2018. Unlike all other super payments, FHSSS withdrawals will not be split into taxable and tax-free components. Rather, they will be divided into an amount of non-concessional contributions and an amount of concessional contributions plus earnings.

The first step for a member looking to make a withdrawal under the scheme is to apply to the ATO for a determination. The tax office’s determination will tell the member the amount, and contribution split, of their maximum FHSSS withdrawal.

Under current processes, contributions are reported annually by SMSFs with the due date for the SMSF return commonly the end of the following February. This means that, depending on when the member requests the FHSSS determination, up to 20 months of contributions may not be recorded by the ATO.

The tax office will provide more information as 1 July 2018 approaches, however, interim contribution reporting by the SMSF or the member may be required to ensure all eligible FHSSS contributions are captured.

Everything is in order

ATO determinations will include eligible FHSSS contributions in the order they were made. Where both concessional and non-concessional contributions were made at the same time, the non-concessional contributions will be taken to have been made first.

This means any eligible FHSSS contributions made from 1 July 2017 will be counted in the order they were made, even if they weren’t contributed with the intention to withdraw them under the scheme.

Example

Cecilia has had a standing arrangement where $1000 of her salary is sacrificed to her SMSF each month since 2015. In June 2019, she visits her financial adviser, Derrick.

Derrick suggests she make non-concessional contributions of $15,000 for each of the next two years with a view to withdrawing them to help purchase her first home. He says it is important Cecilia’s FHSSS withdrawal is made up of non-concessional contributions to ensure it is not reduced by contributions tax.

Cecilia follows Derrick’s advice, but gets a shock when the ATO’s determination shows her maximum withdrawal consisting mainly of concessional contributions. Derrick did not realise her salary sacrifice contributions in 2017/18 and 2018/19 were the first eligible FHSSS contributions she made, and hence are the first counted for her withdrawal.

The ATO needs to know

Current annual SMSF reporting does not identify the date a contribution was made. This means that, within the same financial year, there is no way for the ATO to work out whether concessional or non-concessional contributions were made first for FHSSS purposes.

No doubt greater guidance on how the ATO will manage this issue will be provided. A potential outcome may be the ATO requiring more detailed contributions reporting.

Plus earnings

Earnings associated with withdrawn contributions are also able to be withdrawn. These associated earnings are calculated as accruing daily at the rate of the shortfall interest charge (SIC) applicable for that day. In the past two financial years, the SIC rate has moved between 4.70 per cent and 5.01 per cent a year.

Withdrawal mechanics

Once the member has received their ATO FHSSS determination, they can apply to the tax office to make a withdrawal. The request will need to be made in the approved form and, upon receipt, the ATO will issue a release authority to the member’s super fund to get the FHSSS amount released to the tax office. The ATO will then withhold tax appropriately before paying the net amount to the member.

It is important an SMSF’s trust deed permits amounts to be withdrawn under the scheme. In some cases, this may require an amendment to the trust deed.

Taxing times

The amount of FHSSS withdrawal attributable to non-concessional contributions will be tax-free. Concessional contributions plus earnings will be taxed at the member’s marginal tax rate with a 30 per cent tax offset applied. The offset is non-refundable and cannot be carried forward to future years.

Example

Shane has made $20,000 in FHSSS eligible concessional contributions. He applies to withdraw this full amount, less contributions tax, plus associated earnings. This provides him with a before-tax withdrawal amount of $17,698.

Shane will pay tax at his marginal tax rate of 34.5 per cent (including Medicare levy) with a 30 per cent offset applied. This will result in $796 in tax, leaving him a net withdrawal of $16,902 to put towards the purchase of his first home.

Buying the home

The amount withdrawn under the scheme must be used to purchase or construct the member’s first home. The contract must be entered into within 12 months of the FHSSS funds being released and the member must intend to live in the home as soon as practicable for at least six of the first 12 months the home is habitable. The commissioner of taxation has discretion to extend the 12-month time period to a maximum of 24 months.

If the FHSSS withdrawal is not used in an approved fashion, penalty tax is charged at a rate of 20 per cent on the concessional contributions plus earnings amount.

If the member does not purchase their first home as originally intended, they may recontribute the concessional contributions plus earnings amount, less the tax withheld by the ATO, back into super to avoid the penalty tax. This recontribution must be in the form of non-concessional contributions and must be made within the 12-month period.

The benefit

In most of Australia’s capital cities, even the maximum amount able to be released under the scheme, potentially over $30,000, will not, of itself, be enough for a deposit on a home. That said, it can be a very tax-effective element of a greater strategy. It can also be a stand-alone approach to saving for a deposit where multiple buyers are combining their funds (such as in the case of couples or siblings).

Example

Irma, 29, is saving to purchase her first home. She is on the 32.5 per cent marginal tax rate. She salary sacrifices $15,000 a year for two financial years and withdraws that amount, less the contributions tax of $4500, to purchase her first home.

Irma’s $25,500 of concessional contributions withdrawn is taxed at her marginal rate with a 30 per cent offset applied. This will result in Irma paying tax of $8798 with an offset of $7650 applied. Her net tax on the withdrawal is $1148. Thus, she has $24,352 to use in her first home deposit.

By contrast, to save $24,352 towards the deposit on her first home outside super, she would need to use $37,179 of pre-tax salary. By using the scheme, she has used $7179 less in pre-tax salary in order to save $24,352.

Note: Earnings have been ignored in this example.

The higher the marginal tax rate, the higher the saving

Using concessional contributions under the scheme becomes more tax-effective the higher the member’s marginal tax rate. Table 1 compares the benefit where $15,000 in concessional contributions are made each year for two years. Earnings are ignored and, where multiple buyers are involved, they can each make the savings shown.

A helping hand

Where parents are looking to help their children buy their first home, the scheme can also be a useful tool. Rather than simply providing a lump sum to their child, parents can subsidise their child’s income while the child takes advantage of tax-effective salary sacrifice or personal deductible contributions.

Example

Catherine is keen to help her daughter, Gillian, purchase her first home. Gillian is saving hard, but Catherine would like to give her efforts a $10,000 boost.

Catherine plans to provide the money to Gillian directly, however, her adviser suggests she might want to help Gillian through the FHSSS. Gillian pays tax at the rate of 34.5 per cent (including Medicare levy). Catherine’s adviser suggests she subsidise Gillian’s income for a year while Gillian salary sacrifices the equivalent amount to her super to be withdrawn later under the scheme.

As such, Catherine gives Gillian $833 a month to help pay her lifestyle expenses. Gillian sets up a salary sacrifice arrangement with her employer to sacrifice the equivalent pre-tax amount of $1273 per month.

When she goes to buy her first home, Gillian will be able to withdraw 85 per cent of the first $15,000 for the year, or $12,750, under the scheme. This withdrawal will be subject to $1221 in tax after the 30 per cent offset is applied.

By using the scheme, Catherine has added $11,529 to Gillian’s deposit, $1529 more than would have been the case had she given Gillian $10,000 directly.

Note: Earnings have been ignored in this example.

The rub

Engaging younger clients and fund members with their super savings can result in profound benefits, far beyond the important purchase of their first home. The opportunities presented by the FHSSS are significant, but they require a sound knowledge of the rules and restrictions of the scheme.