The changes to the superannuation system handed down in this year’s federal budget have been the most significant for a long time. Michael Hallinan explains how the practical application of the new rules will work.

The changes proposed in the federal budget are the most significant changes to superannuation since those made a decade ago by then-treasurer Peter Costello. Of the 15 changes, the most significant are catch-up contributions, the $500,000 lifetime non-concessional contributions cap and the $1.6 million pension transfer cap. These changes will drive superannuation strategies going forward. Clearly, in the Scott Morrison super world, the principal planning issues will be to equalise super balances between couples and understanding the application of the pension transfer cap. The other changes are unlikely to give rise to as many technical issues as the pension transfer cap.

Of the various changes, which will have the greatest impact on contributions? This is likely to be the $500,000 non-concessional contributions cap. The impact of this cap is far greater than the reduction in the concessional contribution cap from $30,000 (or $35,000) to $25,000. While the lifetime contributions cap will have the greatest financial impact of the various changes, the pension transfer cap will generate the most technical issues and be the most demanding of advisers’ time.

The big three changes

Catch-up contributions

The proposal is to permit unused concessional contributions to be carried forward for up to five years. However, to use the carry forward, the member concessional contributions made must exceed the concessional contribution cap for the current financial year. The excess of the contributions (catch-up contributions) can then be applied against the carried forward cap. Secondly, in respect of the financial year in which the catch-up contributions are made, the member must have a superannuation balance of less than $500,000.

Before illustrating the operation of catch-up contributions, the following points must be noted. First is that the taxpayer must exhaust the concessional contribution cap for the current year before making catch-up contributions.

Second, the taxpayer must have satisfied the $500,000 balance test in respect of the financial year in which the catch-up contributions are made. Third, the $500,000 balance test is a global test and applies to all superannuation balances of the member (accumulation and pension). Fourth, it is yet to be announced whether death benefit pension balances are to be counted. Finally, the relevant balance date is most likely to be a historical balance of say the opening balance of the immediately preceding financial year.

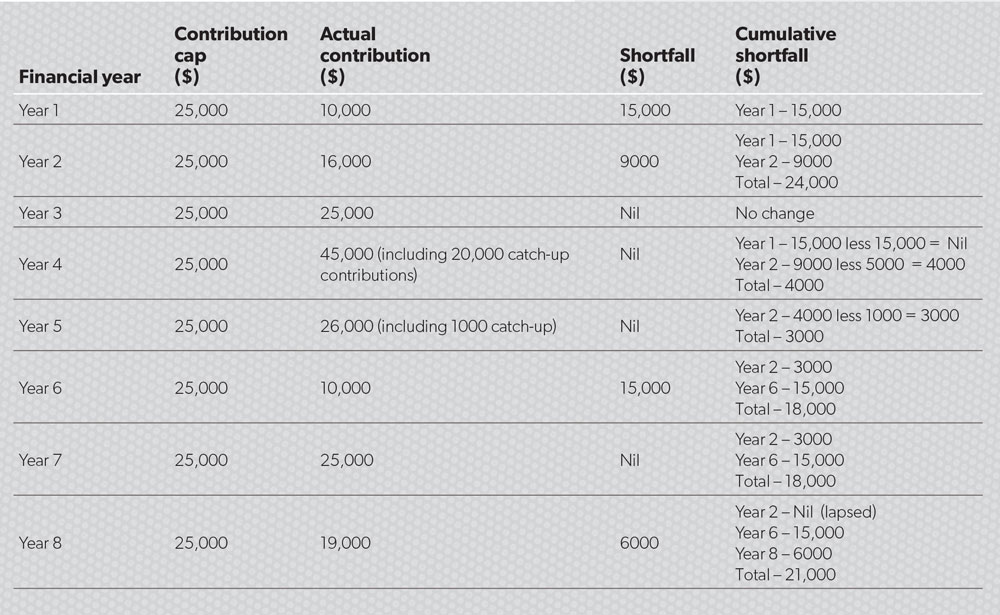

The operation of catch-up contributions is set out in table 1.

Table 1: Operation of catch-up contributions

To date no information has been given as to whether the $500,000 super balance used to determine eligibility to make catch-up contributions is to be adjusted for benefit withdrawals, pension commencements or family law splits.

Presumably if the aggregate super balance falls below $500,000 due to negative investment returns, the taxpayer will be entitled to make catch-up contributions. However, if the aggregate balance falls below $500,000 due to benefit withdrawals, this would not permit the taxpayer to be entitled to make catch-up contributions. It is presumed the aggregate balance includes pension balances of the taxpayer. However, what is the status of a family law payment split that reduces the balance to below $500,000?

If the super balance is to be adjusted for benefit withdrawals, then they must be added back to the balance. Further, is there any adjustment for the time the withdrawal has been out of the system? A system that requires adjustment to the super balance for withdrawals will have to track all withdrawals, including pension payments, and will have to distinguish between withdrawals from benefit rollovers (to avoid double counting).

If a super balance has been reduced to below the $500,000 balance by reason of a benefit split under the family law splitting provisions, is the benefit split to be treated as an add back to the taxpayer’s balance or is it to be treated as an increase to the super balance of the former spouse? If the former, then the taxpayer has ceased to be entitled to make catch-up contributions, yet has a reduced balance. If the latter, then the spouse may now be disentitled to make catch-up contributions, while the taxpayer may not be entitled to make catch-up contributions.

Treasury may be alert to the practical difficulties of permitting the super balance to be adjusted (it may still have a living corporate memory of the adjustment of reasonable benefit limit determinations) and simply provide that once the super balance of a taxpayer exceeds $500,000, the ability to make catch-up contributions is lost.

Lifetime $500,000 cap

The change is to impose a $500,000 lifetime cap on non-concessional contributions. The cap will be indexed in increments of $50,000 and indexed by reference to average weekly ordinary time earnings.

While the cap applies immediately (from 7.30pm AEST on 3 May 2016), all non-concessional contributions made since 1 July 2007 will be counted for the purposes of the cap. Consequently some taxpayers will have a zero cap going forward as the $500,000 lifetime cap will have been exhausted by non-concessional contributions made in the period 1 July 2007 to 3 May 2016.

This is probably the most detrimental of the budget changes. By way of comparison, under the Costello super system, an individual could have contributed $7.2 million to super as non-concessional contributions. (This assumes a 40-year horizon, no indexation of the $180,000 cap and excludes capital gains tax (CGT) and personal injury contributions). Under the currently proposed super changes, the same taxpayer will be restricted to $500,000 of non-concessional contributions.

The $500,000 lifetime cap applies separately to each taxpayer. Consequently a taxpayer cannot apply excess non-concessional contributions to their spouse and/or use the unused non-concessional contribution cap of their spouse.

Going forward, key strategies for married couples will be to ensure each has fully used their own non-concessional contribution caps through a combination of spouse contributions and withdrawal and re-contribution strategies (using the abolition of the work test for taxpayers aged 65 to 75).

For taxpayers who own businesses (or who intend to own businesses), a key strategy will be to ensure proper structuring advice is obtained so they are not precluded from qualifying for the small business CGT concessions.

Exhaustion of the lifetime contributions cap will be measured in percentages rather than dollar amounts. This precludes the application of a strategy of living $1 under the cap to take advantage of future indexation of the cap.

Explanation

The exhaustion of the lifetime $500,000 cap is measured by percentages to preclude the possibility of a taxpayer leaving a $1 shortfall to access the dollar increase in the lifetime arising from indexation.

Impact of family law payments on the lifetime cap

What is the impact of family law benefit splits on the $500,000 lifetime non-concessional contributions cap? If a base amount is allocated to the spouse of the taxpayer, is the lifetime cap of the taxpayer adjusted to reflect the diminution of the taxpayer’s superannuation balance?

For example, Bill has a superannuation balance of $800,000, which includes $500,000 of non-concessional contributions. He has exhausted his $500,000 lifetime cap. Beryl, Bill’s spouse, is allocated a $500,000 base amount. Beryl has no superannuation and consequently a full entitlement to her lifetime cap of $500,000. After the allocation of the base amount, Bill’s super balance is $280,000 (after reduction by the adjusted base amount of $520,000) and Beryl’s superannuation balance is now $520,000. Unless there is an adjustment to Bill’s lifetime contributions cap, he has a zero cap, while Beryl has full access to her lifetime contributions cap.

Until the finer details of the operation of the lifetime non-concessional contributions cap are released, family law practitioners will need to take into account both spouses’ positions in relation to the lifetime contributions cap. If the design of the legislation is that the lifetime contributions cap cannot be adjusted to take into account a family law split, then splitting non-superannuation assets may be more attractive than splitting superannuation assets. At the very least, family law practitioners will need to advise their clients of the implication of a base amount split to their lifetime non-concessional contributions cap.

$1.6m pension transfer cap

From 1 July 2017, a cap of $1.6 million will apply to the amount of superannuation that can be transferred from accumulation to pension phase. The cap will be a lifetime cap and will be indexed to the consumer price index and adjusted in increments of $100,000. The cap will apply to both existing and future pensions. Any excess super transferred into pension phase must be returned to accumulation phase.

The financial impact of this change will not be as significant as the financial impact of the $500,000 lifetime non-concessional contributions cap. However, this change is likely to generate far more technical and strategy issues than the $500,000 lifetime cap.

Transitional aspects

For pensions in force at 30 June 2017, the excess pension account balance will have to be rolled back to accumulation phase or cashed out. If rolled back, the earnings on the excess will be taxed at 15 per cent.

Presumably all super funds will have to advise the ATO of their pension account balances as at 30 June 2017 and the tax office will then have to aggregate the pension balances for each taxpayer and determine the extent to which the aggregate balances exceed $1.6 million transfer cap. The excess will have to be returned to accumulation phase or cashed out.

Given the time it will take to identify and aggregate each pension interest of a taxpayer, it is likely the implementing legislation will impose a charge to reverse the effect of tax-free earnings of the excess pension transfer in the period from 1 July 2017 until the transfer takes effect.

Comments

This is a cap on the amount of superannuation that can go into pension phase: not a cap on the amount of superannuation in pension phase. Consequently, once a super balance passes the transfer cap, the fact the super balance in pension phase subsequently exceeds $1.6 million due to investment earnings is irrelevant.

No tax will be imposed on the transfer back of excess pension balances. However, given the likely delay in effecting an excess pension transfer balance (say on 1 July in financial year one) and the ATO determining that the transfer cap has been exceeded (say sometime after the SMSF has lodged its annual return for financial year one), it is likely a charge will be imposed to reverse the effect of the earnings tax exemption on the excess pension transfer. This charge may be imposed on the fund or on the member.

The use of the pension transfer cap will be measured in percentages rather than dollar amounts. Consequently the strategy of leaving $100 spare in the pension transfer cap (that is, using only $1,599,900 of the transfer cap) will not preserve access to the full value of any indexation of the pension transfer cap. For example, if the pension cap is used to 99 per cent (leaving 1 per cent spare), the entitlement to any indexation will be 1 per cent of $100,000 and not the full $100,000.

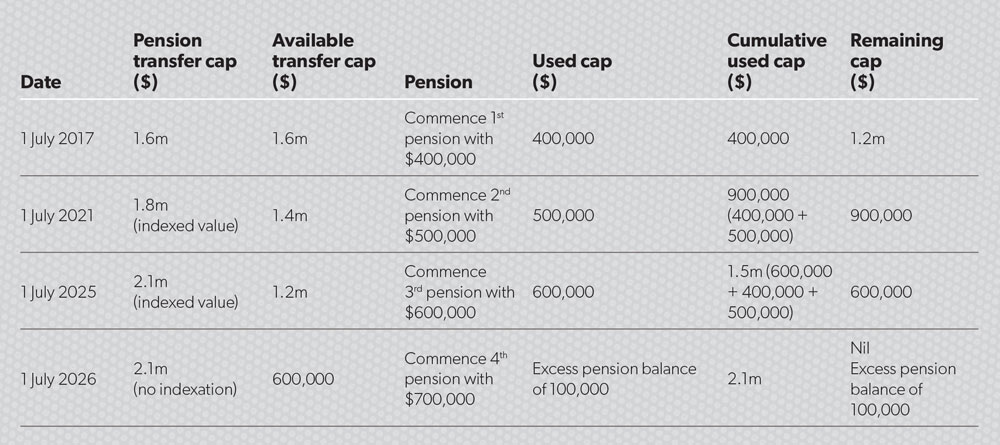

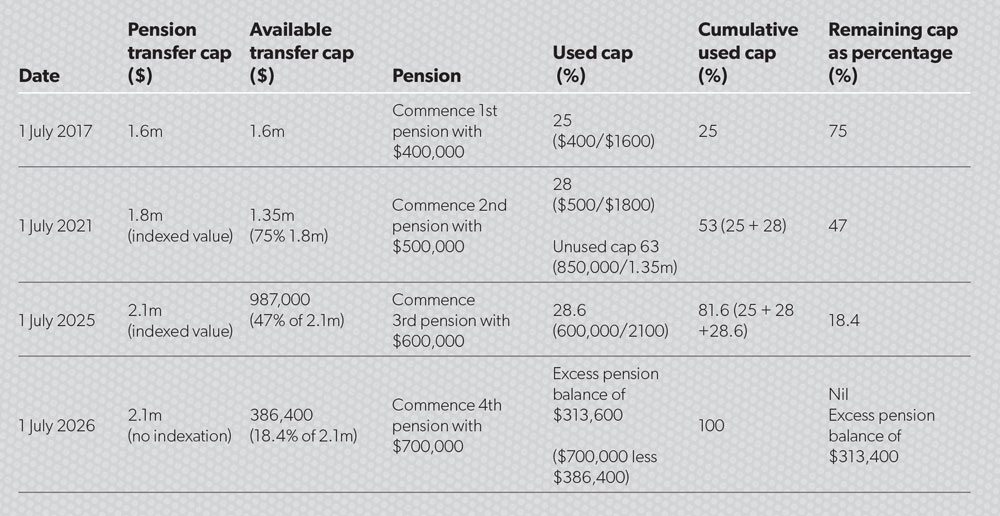

Measuring the utilisation of the pension transfer cap in percentage terms has the effect of watering down the impact of any subsequent increase in the value of the pension transfer cap. This impact is illustrated in tables 2 and 3.

Table 2: Indexation and dollar counting

Table 3: Indexation and percentage counting

Note: This table has been constructed on one approach of the proposed percentage counting method (which is consistent with the four-line explanation provided in the budget materials). The legislation may adopt a different approach.

Table 2 assumes there is both indexation of the pension transfer cap and that the utilisation of the cap is measured in dollar terms. Table 2 assumes there is both indexation of the pension transfer cap and utilisation of the cap is measured in percentage terms. Both tables assume the same pension commencements. By way of comparison, and given the same history of pension commencements, the dollar counting method will recognise a $100,000 excess pension transfer while the percentage counting will recognise $313,400 excess pension transfer.