Gold has attracted a lot of negative publicity in recent times, but Jordan Eliseo says there is a compelling case for investing in physical gold.

Gold has had a tough start to the year, with prices correcting 15 per cent from US$1664 at the end of 2012 to US$1420 at the time of writing. At one point in early April, it touched as low as US$1320 as two days of panic selling on futures exchanges saw the precious metal suffer its largest drop in 30 years.

Figures from goldprice.org show while a lower Australian dollar has partially protected domestic investors from this fall, a year-to-date return of -9.3 per cent is some way short of the 11 per cent a year returns generated on average since 2004.

The pronounced sell-off in gold has led many in the mainstream financial media, as well as more traditional asset managers, to proclaim the end of the decade-long secular gold bull market.

My experience as an investor in precious metals since 2003 leads me to advise SMSF investors to do some research before accepting this conclusion.

Corrections of similar magnitude in gold occurred in 2006 and 2008. Those corrections, instead of spelling the end of the precious metal bull market (as was claimed erroneously at both those points), actually ended up being the perfect entry points for investors looking to diversify and protect their portfolios with an allocation to precious metals.

More importantly, the reasons given for the April correction, such as investment banks being bearish on gold, Cyprus perhaps needing to sell gold to pay for debts, and institutions selling their exchange-traded fund (ETF) gold holdings, are in no way evidence that the secular trend has occurred.

While investment banks did issue negative reports on gold, it must be stressed that, by and large, most of them have been bearish for the majority of the bull market, constantly predicting lower prices into the future. In fact, Societe Generale, one of the major gold bears, predicted gold would fall to below US$600 in 2008 after a correction similar to the one we are witnessing today.

As for Cyprus being forced to sell its gold, there are two points worth discussing here. First, it’s a sure sign of what’s really going on in the economy and our financial system when institutions such as the International Monetary Fund want physical gold, not financial instruments, as payment or collateral. Why would it want gold if it thought its value would fall in the years ahead? Secondly, even if Cyprus sold its gold today, it would cover barely 3 per cent of its US$20 billion debt load. It’s a similar metric for other troubled European nations, such as Italy and Spain.

For the two largest debtor nations, Japan and the United States, their gold holdings would only cover between 0.3 per cent and 2.5 per cent of their debt obligations at today’s prices.

Finally, while ETF outflows have hurt the gold price, they’ve been more than offset by physical buying, with imports into China and India running at hundreds of tonnes a month in March and April.

Therefore, while we can’t deny gold has had a serious correction, the rationale behind that correction doesn’t in any way indicate the end of the bull market, and should instead be looked at as a buying opportunity.

There are two reasons for this, the first being that at US$1420 in today’s money, gold is still cheap by historical standards, and a long way from a bubble. The second is that we are still in the perfect macroeconomic environment for gold prices to appreciate.

Let’s deal with each of these issues in turn.

No gold bubble

Even though gold is not the bargain it was a decade ago, comparisons with history highlight it is nowhere near a bubble, and significant upside potential remains.

There are a number of metrics used to measure the current gold bull market versus previous ones, including the last mega precious metals bull market in the 1970s. These include a multiple of the return seen in the 1970s (up by over 25 times), an ‘apples with apples’ inflation adjustment, dividing the US money base by US gold reserves, or pricing gold at a 1:1 ratio with the Dow Jones Industrial index, a metric that has been reached at every gold bull market top of the past 110 years. All of them show that, if history is any guide, gold is nowhere near a bubble at today’s prices.

While we are not necessarily predicting prices of between US$6000 and US$16,000, the fact gold prices have gone this high in previous bull markets should give individuals considerable encouragement that there is still time to invest in precious metals, with potential returns of 500 per cent plus from current prices.

The perfect macro environment

Ultimately though, gold is a monetary asset. That’s why central banks own it. It competes with the paper money we are paid with, use in daily commerce and store in bank accounts.

Therefore, to end a bull market in gold, central banks will need to raise real interest rates significantly, creating an opportunity cost for investing in gold, which as its critics only too happily point out, pays no yield.

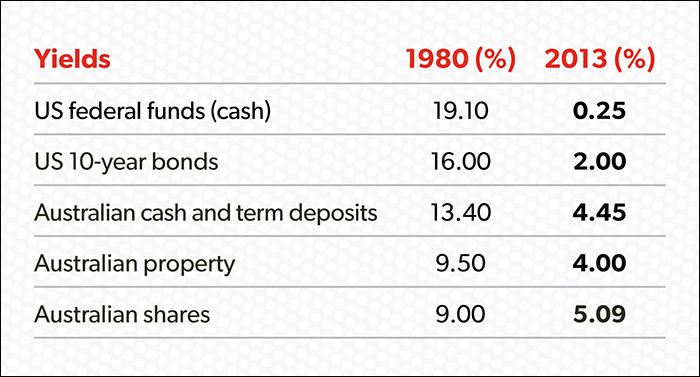

This is what happened in the 1980s, the last time gold was in a bubble. As table 1 shows, yields on financial assets back then were very attractive, highlighted by the fact you could get over 13 per cent in an Australian bank account. In 2013, it’s a very different story, with yields on offer around the world for shares, bonds and property barely in line with inflation.

And despite mainstream media claiming the economy will improve and rates will normalise in coming years, trustees shouldn’t bet on it. Higher interest rates would pose a huge problem for an over-indebted private sector. More importantly, they’d cause havoc with government finances.

Table 1

In Japan, for example, over 25 per cent of tax revenue is spent on interest on the national debt, despite average borrowing costs well below 1 per cent.

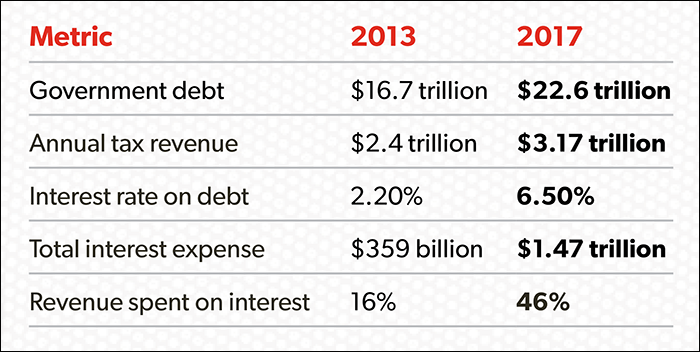

The story is not much better in the US, where public finances are also in a mess. As table 2 highlights, by 2017 the US government could well owe US$22.6 trillion. If, by that time, interest rates were to have risen to 6.50 per cent, the long-term average before the global financial crisis (GFC), then the US government would be spending 46 per cent of every tax dollar merely servicing the national debt.Bear in mind that non-discretionary items of the US budget, such as social security and Medicare, already consume more than 100 per cent of tax revenue, and are set to grow rapidly with the aging population in the years ahead. An increase in servicing costs on the national debt will prove impossible for the US government to honour.

The US, Japan and indeed most developed market sovereign nations are stuck. Either they pare back their gross overspending, cut the welfare state and cause a recession that will likely be far more significant than the GFC, or keep running unprecedented deficits.

Table 2

The only way to pay for those deficits will be by allowing central banks to print money perpetually. This is the road they will continue taking, as it is the most politically acceptable way of ‘defaulting’ on a debt burden that can’t ever hope to be repaid, and which gets worse by the day.

The real economy

Getting a read on the real economy looking at short-term data, such as consumer confidence, retail sales and industrial production, is difficult, as these numbers oscillate on a monthly basis.

A better understanding is gained when one looks at the longer-term employment statistics out of Europe and the US, both of which paint a sobering picture.

According to portalseven.com:

- European unemployment is at a new record of 12.1 per cent, nearly 3 per cent higher than when the GFC officially ended. Youth unemployment is over 25 per cent across the continent.

- US unemployment, as measured by the U-6 rate (which includes discouraged and part-time workers), is 13.9 per cent today, some 5 per cent higher than 2007, and far worse than the official 7.5 per cent number we see in the mainstream media.

- While rising stock prices are nice to see, trustees shouldn’t forget that globally the real economy continues to suffer greatly under the burden of too much debt, and any investor with a portfolio built around the recovery is taking huge risks with their capital.

How about Australia?

Australia really has been the lucky country. Over two decades of economic expansion and the only developed nation to avoid recession during the GFC, it’s no wonder it’s often been referred to as the miracle economy.

However, whether it’s forecast deficits in the latest federal budget, the huge wind back in capital expenditure plans in our mining sector, a plunging dollar or the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) needing to cut rates below the ‘emergency lows’ of the GFC, it’s quite clear all is not well with the Australian economy and we face serious challenges in the decade ahead. The following elements have been identified by macrobusiness.com.au:

Adjusting to the unwinding of the mining capital expenditure boom that grew by over 6 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the past decade.

Reviving a manufacturing sector that has been in outright contraction for years.

A private sector debt burden, over 100 per cent of GDP, that is considerably higher than other western nations, which ran into huge problems when the GFC hit.

A housing market that is no longer responding to low rates in any meaningful way.

While the great hope of the RBA, and the government, is that a weaker Australian dollar and lower interest rates will kick off a boom in the non-mining economy, with private sector debt levels where they are, and with the outlook for employment highly questionable, that boom is unlikely. Instead, a lower Australian dollar will trigger higher inflation through higher import costs, with domestic or ‘non-tradeable’ inflation already running around 4 per cent a year.

This will be a double whammy for SMSF investors, who will see inflation rise, while the return they receive on their term deposits will fall with a lower cash rate.

So what’s an SMSF trustee to do?

The most important thing all trustees can do is acknowledge the reality of the economic challenges we face, and the historically questionable path governments and central banks are leading us down. We are in the worst environment for wealth creation in over 100 years. Therefore, wealth protection should be the name of the game, as in times like these, return of capital should be as important as, if not more important than, return on capital.

This is where physical bullion comes in, as no asset class has a better track record of wealth protection in environments like the one we are in today and will be in for the foreseeable future. Despite its daily volatility, in environments of low to negative real interest rates, gold historically appreciates at 10 per cent or better per year.

That, coupled with the fact it diversifies risk away from a portfolio dominated by shares, term deposits and property, makes it an attractive investment for any trustee looking to protect their wealth through this difficult period.

Why physical gold

While ETFs, gold miners and contracts for difference give exposure to the gold price, only physical gold will provide the capital appreciation one can reasonably expect in this environment, as well as the removal of counterparty risk.

Considering the leverage in our financial system, this final benefit should not to be overlooked.