While SMSFs show a traditional bias toward domestic equities, developments in other economies mean investing in overseas shares is now worth further consideration. Chad Padowitz examines the case for international shares from several angles.

The solid performance of global equity markets during the 2013 financial year, including the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), has at long last resulted in domestic investors starting to return to equity investments.

It is almost impossible to identify the start of a bull market, unlike the end of one, which often get special names such as Black Tuesday, but having experienced a good nine or 10 months of continuous positive returns, many Australian investors are feeling more confident about allocating money into equities.

This is good news because equities form a vital component of any portfolio, especially any portfolio with a long-term strategy, such as a superannuation fund, and almost all investors should have exposure to equity markets. More buoyant equity prices may also lead to higher economic activity as chief executives and boards feel more comfortable in making investment decisions.

Equities are a key source of growth in any investor’s portfolio, although unfortunately the volatility and recent credit and sovereign crises have scared many investors into staying on the sidelines.

However, with other investment options, such as sovereign bonds and term deposits, offering markedly lower returns, equities have greater appeal. Indeed, The Financial Times in May 2012 noted: “Once investors bought government bonds for a risk-free return. Today, they’re buying return-free risk.”

Another encouraging sign is that more investors are starting to recognise there is more to equity investments than the Australian share market.

Traditionally, Australian investors have been very focused on domestic shares. This is understandable. Before the global financial crisis, the Australian market performed extremely strongly, delivering unprecedented returns to investors, with no foreign exchange risk. And for most investors it is much easier to invest in a company you feel you know and perhaps buy from, than those that are less familiar.

However, this somewhat parochial view is starting to change. There are a few drivers for this:

- The Australian share market has lagged other developed world share markets in the past few years. While the S&P 500, for example, has climbed since August 2011, and in March 2013 hit a new all-time high, the ASX 200 is still well off the peak reached in May 2008.

- The Australian market is extremely small compared to others around the world. It makes up just 2.6 per cent of the global market, compared to the United States (around 50 per cent) and the Tokyo stock exchange (7 per cent).

- The Australian share market lacks the depth and breadth of other equity markets, being dominated by financial companies and resource stocks, and the largest companies dominating the rest of the market. To that end, the ASX 20 accounts for more than 50 per cent of the total Australian market capitalisation. Once investors hold shares in the major banks and one or other, if not both, of the two biggest mining companies, they already own a significant proportion of the index, with little opportunity for finding outperformance or growth opportunities.

- International equities offer exposure to sectors that are under-represented on the Australian Securities Exchange, such as multinational consumer goods and global pharmaceuticals.

Furthermore, it seems the rise of investment approaches such as exchange-traded funds and the increased access to global investment managers have made international markets more accessible to Australian investors.

For investors who are considering investing in international equities, there are two main investment philosophies.

One is to take a geographic view, selecting regions or even countries that investors regard as attractive and have good potential, for example, investing in managed funds that focus specifically on Asian markets.

The other approach is to look at particular sectors or companies, regardless of geographic location. Again, there are managed funds that focus on, for example, the information technology sector.

A third option is to invest in global funds. These funds invest in companies anywhere in the world based on high-conviction views.

Geographic view

Despite some blips, the steady recovery in global equity markets continues, albeit with some anomalies such as China. Across the board, equity markets have had a generally good run and there is a positive feel toward them. Some considerations for investors are set out below.

US

Most of the data coming out of the US – including housing, employment and interest rates – is positive, and the Federal Reserve has committed to keeping interest rates low until unemployment falls to 6.5 per cent. Coupled with the shale oil and gas revolution, which is lowering energy costs, these indicators put the US among the best-placed global economies for the immediate future. Growth is still at low levels, but the economy is recovering and there is a sense the worst is over.

Investors are benefiting, with the S&P 500 up by more than 11 per cent since 1 January, and investors are anticipating a supportive earnings season in the US will support further positive returns.

One area of concern is the failure to agree on a budget deal, which saw the first round of automatic spending cuts begin in March. This year will see $85 billion in cuts, and another $900 billion through to 2023. It is possible, and even likely, that this will be altered, but if not, these cuts will materially lower growth over the next few months. And even this headwind, compared to the problems in Europe and Japan, is relatively manageable, particularly in a $15 trillion economy.

Europe

Europe remains the problem child of global economies.

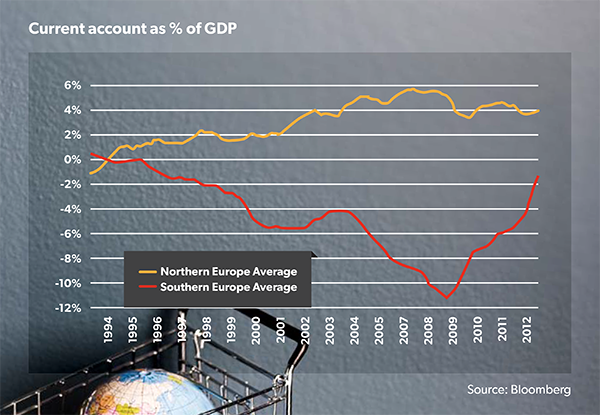

At first glance, the economic problems of Europe appear to be receding. Sovereign bond yields in southern Europe have generally fallen, current account deficits have been meaningfully reduced and European markets are up 6.4 per cent in 2013. Chart 1

illustrates the ‘improvement’ in southern European economies. Northern Europe includes Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and Austria. Southern Europe includes Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain.

Graph 1

As European governments are now largely unable to afford Keynesian-type stimulus programs and position their economies for growth, austerity has become the only option. Hence it is no surprise a low-growth outlook for Europe is the prevailing consensus view.

Nonetheless, there are still cracks in the European Union and the problems that first came to light in 2007 are still unresolved six years later.

We continue to see last-minute deals and weekend bailouts, with no consistency of policy or sense of a long-term plan to resolve the crisis, and it seems people may be becoming blasé about each crisis. Indeed, complacency could end up being the biggest danger to the eurozone, particularly if it results in politicians avoiding the tough structural reforms required.

High unemployment, low growth and democracy are dangerous bedfellows and it should be of great concern that mature democracies are turning to anyone who promises anything other than the prevailing German-led austerity. As the immediate European risk transitions from sovereign debt issues to social and democratic challenges, we believe significant tail risks remain embedded in many European economies and in some cases have actually increased as an unintended consequence of austerity.

The most recent crisis in Cyprus evidenced this. Like Iceland and Ireland, Cyprus was a small economy with an outsized banking sector. The original bailout plan called for a ‘tax’ on all depositors and was successfully resisted due to popular protests and weak political will. This added to the uncertainty and potentially provided a precedent for larger, more important economies such as Spain and Italy.

Sector View

There are a number of sectors that investors in international equities could benefit from.

For example, we are currently seeing attractive opportunities in the energy and healthcare sectors.

Healthcare in particular is likely to be a good long-term story for investors. The healthcare sector is traditionally seen as a defensive sector, because it is less dependent on economic cycles than other sectors. In developed countries with an ageing population – including Australia, but also much of Europe, the US, and parts of Asia such as Japan – the demand for healthcare goods and services will only increase in the next few decades.

However, for investors and trustees seeking a diversified, long-term strategy to include international equities in their SMSF portfolio, managed funds are likely to be the most cost-effective and efficient approach.