Having a plan to dictate what happens to an SMSF upon the death of a member is very important. As Daniel Butler and Shaun Backhaus explain, establishing a good succession plan involves getting several elements of the fund right.

There are many strategies put forward on how to provide smooth and effective succession for SMSFs. Fortunately, while there is no one-size-fits-all solution, there are a number of strategies that are simple and cost effective that can substantially bolster your position and set the foundations for SMSF succession.

Your personal estate planning must also be consistent with your SMSF succession plans. Obtaining expert advice and implementing a tailored succession plan is the best way forward for smooth and effective succession, especially with the increased emphasis on technological development and commoditisation of the SMSF industry. It is also critical to obtain documents and advice from suppliers who have the appropriate expertise as the most appropriate strategy must consider the background circumstances of each member.

We now venture into the basic to the more advanced stages of SMSF succession planning.

Sole purpose corporate trustee

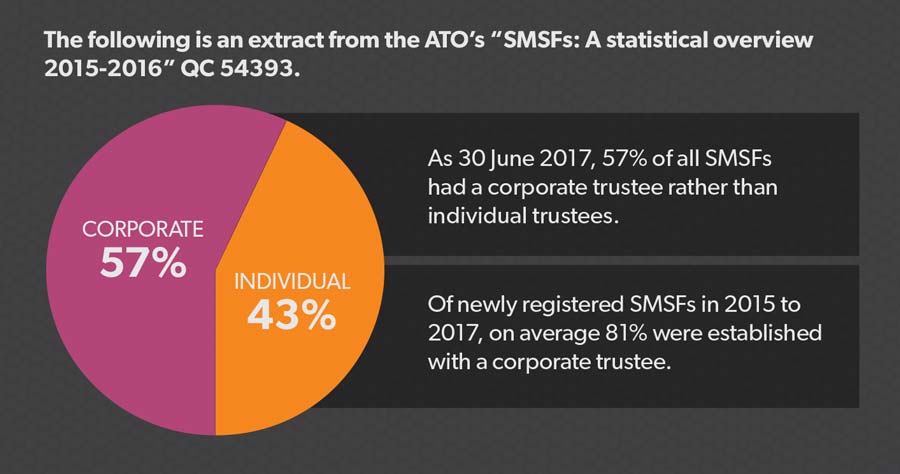

We strongly recommend an SMSF have a sole purpose corporate trustee rather than individuals as this greatly enhances succession. The upfront cost of establishing the company generally results in long-term benefits that far outweigh that cost. These are conveniently summarised on page 28.

Despite the numerous compelling reasons outlined on page 28, around 43 per cent of SMSFs still have individual trustees. This is surprising considering the many long-term advantages of having a corporate trustee.

The administrative penalty regime introduced in mid-2014 can now result in an administrative penalty ranging from $1050 to $12,600 for each offence (reflective of $210 per penalty unit that applies from 1 July 2017). Importantly, here the penalties are imposed on a per head basis for individual trustees. In contrast, the directors of a company are only jointly liable to one penalty per offence. Thus, if an SMSF loan is made to a member or related party, and if there are two individual trustees, the minimum penalty is $25,200 (compared to $12,600 for an SMSF with a corporate trustee).

Loans to members/related parties are consistently noted by the ATO as one of the main contraventions reported in auditor contravention reports (ACR) lodged with the ATO each year. The ATO’s QC 54393 notes 7600 SMSFs had ACRs lodged with 14,800 contraventions in the 2017 financial year.

Administrative penalties are now being imposed on SMSF trustees on a regular basis and we have seen the ATO seek to impose administrative penalties in position papers up to $600,000. Thus, for many SMSFs it is not so much whether they will be subject to one of these penalties, but rather a question of when. The penalty regime is the nail in the coffin for SMSFs with individual trustees.

Moreover, when considering recent legal cases, the merits of having a corporate trustee become very clear. In Katz v Grossman [2005] NSWSC 934 a family relationship between two children (Linda and Daniel) was jeopardised as a result of Linda being admitted as co-trustee on her mother’s (Evelin Katz) death to satisfy the trustee-member rules. Ervin and his wife, Evelin, were the original trustees/members of their SMSF. Shortly after Evelin’s death, Ervin appointed his daughter Linda as the other co-trustee. Shortly after Ervin’s death, Linda appointed her husband, Peter Grossman, as co-trustee and the then trustees, Linda and Peter, decided to pay Ervin’s death benefit of around $1.2 million to Linda. In doing so, the trustees ignored Ervin’s non-binding nomination for an equal sharing of his death benefit between his two children, Linda and her brother, Daniel.

This case could have easily been avoided if a corporate trustee had been appointed, with Ervin gifting an equal number of shares (in the corporate trustee) to each child via his will. In addition, Ervin could have left a binding death benefit nomination (BDBN) paying his death benefit to his deceased estate (that is, his executor as legal personal representative (LPR)).

With so many SMSFs with individual trustees currently managed by mums and dads with children who are waiting in line for succession, Katz v Grossman is a great war story to discuss to encourage families to commence their SMSF succession planning.

Thus, in summary, a corporate trustee is an essential step in the process of SMSF succession planning.

Attorneys and BDBNs

Appointing an attorney under an enduring power of attorney (EPOA) is often a step in SMSF succession planning. In the recent case of Re Narumon [2018] QSC 185, the court considered whether attorneys could validly execute both a BDBN confirmation/extension as well as a new BDBN on behalf of a member. Whether an attorney will have such power will depend on the SMSF governing rules, the EPOA document, the relevant powers of attorney legislation and the federal superannuation legislation.

In Re Narumon the member, Mr Giles, became incapacitated and his attorneys under an EPOA, his wife, Mrs Giles, and his sister, Mrs Keenan, purported to both extend a prior lapsed BDBN and to execute a new BDBN, both of which provided for death benefits to be paid to them. The EPOA document did not authorise the attorneys to enter into a conflict transaction. The court found the extension of the prior BDBN was valid because:

the fund’s governing rules allowed the prior BDBN to be confirmed and provided that any power or right of a member could be exercised by an attorney,

while the EPOA document didn’t expressly deal with superannuation matters, the meaning of ‘financial matters’ in the relevant legislation was wide enough to cover superannuation, and

while a ‘conflict transaction’ entered into by an attorney can invalidate a transaction, the confirmation of the prior BDBN was not held to be a conflict transaction. While the BDBN benefited the attorneys, it was found not to amount to a conflict as it simply ensured the continuity of Mr Gile’s prior wishes.

However, the new BDBN executed by Mrs Giles and Mrs Keenan was found to be a conflict transaction because it provided for a different payment of death benefits that benefited Mrs Giles more than the extended BDBN.

Accordingly, practitioners should consider the wording in each attorney document and the SMSF governing rules. Consideration should also be given to including express wording to make decisions regarding superannuation interests and to enter into conflict transactions when preparing EPOAs.

Why is succession to control so important?

Many lawyers like the old saying that possession is nine-tenths of the law. This expression reflects the reality that even if you do have legal rights, you may have to enforce these at great expense, time delay and uncertainty. In many legal battles, many give up soon after receiving a number of invoices from their lawyers unless they are seeing some tangible progress. Entering the steps of a Supreme Court typically involves a substantial outlay.

The Wooster v Morris [2013] VSC 594 decision is one of the most important decisions to date regarding SMSF succession planning. Namely, what really matters is the identity of who controls the fund on loss of capacity or death.

Mr Morris (the deceased) had two adult daughters from a previous marriage (Mrs Wooster and Mrs Smoel, being the plaintiffs). He also had a second wife, Mrs Morris. The deceased and Mrs Morris were the members and trustees of the SMSF. The deceased made a BDBN in favour of his two daughters.

After his death, Mrs Morris appointed herself as the sole director/shareholder of a corporate trustee. She decided the BDBN in favour of Mr Morris’s two daughters was not binding and, as sole director of the corporate trustee, decided to pay herself the $924,509 death benefit.

The plaintiffs issued court proceedings seeking declarations the BDBN was binding. A special referee found in favour of the plaintiffs, holding the BDBN binding and that the plaintiffs were entitled to be paid the death benefit plus interest. The parties agreed to be bound by the referee’s findings.

Lesson 1 – LPR does not automatically become a trustee

Wooster v Morris clearly dispels the myth that when a person dies their executors (LPRs) automatically become trustees in the deceased’s place. Here the plaintiffs were the deceased’s executors, but they did not become trustees. This point was also confirmed in Ioppolo & Hesford v Conti [2013] WASC 389, where the deceased member’s two executor children were unsuccessful in their case against their mother’s second spouse to be appointed as SMSF trustees following their mother’s death.

The identity of the trustee upon death is determined by the SMSF deed. Unfortunately, there are very few SMSF deeds that appropriately distribute the power to appoint a trustee upon death or loss of capacity.

Lesson 2 – BDBNs are only a partial solution at best

There is a misconception SMSF succession planning is handled by making a BDBN. Wooster v Morris clearly dispels this myth as well, where the deceased had made a BDBN yet the plaintiffs were still obliged to spend years in legal battles in order to obtain any money. While a BDBN can be important, it will not necessarily be complied with. However, there is a much greater opportunity for a BDBN to be effective if a successor can, in essence, stand in the shoes of the deceased to ensure the control of the fund is not simply left to the surviving member(s). Accordingly, while a BDBN can be an important tool in SMSF succession planning, the ‘control’ of the fund is more crucial.

Lesson 3 – what really matters is who controls the fund

Wooster v Morris clearly demonstrates that far more important than a BDBN is the identity of who controls the fund on a member’s death or loss of capacity. As stated above, this depends to a very large degree on the SMSF deed. In Wooster v Morris, the trustee’s legal fees in defending the claim were $302,699 in one year as reflected in the fund’s 2013 accounts.

Thus it is crucial that SMSF members plan succession to their role to cover loss of capacity and death.

How to succeed to control of an SMSF

A key planning element for covering risks on loss of capacity and death is to have a trusted person stand in your shoes as your successor director. This requires planning in advance to ensure the smooth transition to an SMSF. To ensure this occurs, among other things, the following needs to be undertaken:

Select the person who is to become your successor director. Ensure they are willing to act and there are sufficient instructions/wishes documented for them on what needs to be done.

Make sure the person’s will and EPOA nominate the appropriate person that they wish to stand in their shoes. (Basically, an attorney under an EPOA while a person is alive and the executor of a deceased person’s will is their LPR who can act for them in legal and financial matters).

Make sure the EPOA has express power to authorise the attorneys to deal with superannuation and the SMSF deed also has express power to authorise an attorney to act. The EPOA should also have express power to deal with potential conflicts, for example, the attorney can make a new BDBN or revise an existing BDBN to benefit themselves.

Table 1: Corporate versus individual trustees

Check the SMSF deed and the constitution of the corporate trustee to see what steps and documents need completing to appoint the relevant person(s) as your successor director(s). Typically, in addition to that person consenting in writing, they may need to satisfy some other hurdles and it is better to discover these now; otherwise, it may be too late.

It is important to note that if someone has more than one LPR, and they wish to nominate more than one, the voting and decision provisions of the relevant SMSF deed and constitution should be carefully examined. This is because unless there are special provisions to equalise voting, each attorney/executor may have an equal control (for example, if there are two directors, being mum and dad, and dad loses capacity and his two children from his prior relationship are his attorneys, then if these two children become directors, there will be three directors. Unless the constitution is appropriately worded, the two children representing their father can outvote the father’s second spouse). However, the LPR who is standing in for the incapacitated/deceased member should only assume this (one) person’s voting capacity. Thus, if there are two or more attorneys/executors nominated to act jointly, the joint LPRs should only have the equivalent of one vote.

Figure 1: SMSF trustee structure

Note that in the case of a corporate trustee, the decision-making depends in the first instance on what is in the constitution, and not what is in the SMSF deed, despite many deeds seeking to cover this. In most constitutions, directors usually have an equal vote regardless of the number of shares they hold or their account balance in the fund. The casting or deciding vote is generally given to the chairperson of the meeting. (In a mum and dad company, this is generally inappropriate and such constitutions should be avoided. Given most mum and dad companies do not comply with formalities, there is generally no practical mechanism to work through potential deadlocks and how to resolve any dispute about who is the appropriately appointed chair). One solution could be, for instance, if there is a deadlock, the person with the most voting shares can have a casting vote. Again, the shares on issue or the constitution could be tailored to provide such a mechanism.

In so checking the deed/constitution, it is important to consider what voting mechanism applies, for example, are decisions determined by the number of directors, member account balances, shares held in the corporate trustee or via some other method? This is important as the constitution and/or the SMSF deed may need amending if it is not appropriate. For example, if the relevant member has the lion’s share of the fund, and voting is based on the number of directors, then this could give rise to an imbalance if the member with the greater fund balance seeks control over the company’s decisions. One mechanism to work through this type of deadlock would be to give the member with the greater fund balance the majority of voting shares and ensuring the constitution reflects this voting power in director and shareholder decisions. If the constitution is not appropriate, then it should be tailored accordingly.

There are numerous advantages of using a corporate trustee compared to individuals as trustees. However, ultimately, a well-designed SMSF deed is also required. In many SMSF deeds, the majority of members can hire and fire the trustee. Under this type of deed the company could be removed by a majority of members, which does not reflect any member’s account balance in the fund. Thus it is crucial you check the mechanism for changing a trustee to ensure a smooth and planned succession occurs. For example, if you have nominated someone to become your nominated successor director, then the corporate trustee and therefore this person could be voted out soon afterwards if the SMSF deed allows the other member(s) to do so by way of a majority vote.

It is also important to consider who will be the successor shareholder as the shareholders generally hire and fire the directors of a company. (Thus, as you can readily see from the above analysis, SMSF succession involves a review of both the SMSF deed and the constitution and these two need to be consistent in design and implementation of the succession strategy to overcome any conflicts between them arising).

Note that the ATO in SMSF Ruling 2010/2 confirmed a member can nominate more than one LPR to stand in their shoes as a director. However, if there is more than one attorney/executor, your nomination should specify who has first go or you should specify whether they are to act jointly or jointly and severally. Also, a nominated person could well be disqualified if they are bankrupt or if they have ever been convicted of an offence involving dishonesty. Accordingly, one or two substitutes should also be nominated just in case.

On the death of a member, the trustee is responsible for administering the fund, including, where there is a BDBN, the decision as to how the death benefit will be paid out. If the deceased member did not make a BDBN, this decision is generally left to the trustee’s discretion. Accordingly, in the case of a second spouse who is left running the fund, they will have discretion as to how to manage the fund and pay out any death benefit.

Ultimately the best documents and strategies to employ depend on the circumstances of each member. Practitioners must be aware of the options available and document strategies appropriately. Planning now and doing the job properly will reduce the risk of clients’ SMSF savings being subject to costly disputes.