Grant Abbott examines some of the troublesome situations that can arise upon the passing of an SMSF member.

I guess by now any professional dealing with an SMSF has had a client die. It happens and will continue to happen. The trouble for SMSF advisers, accountants and financial planners is that there is such little law dealing with what happens upon the death of a member, from a practical perspective anyway.

Now most advisers have heard of or read section 17A(3) of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) (SIS) Act 1993, which gives us the definition of an SMSF where all members must be trustees or a director of a corporate trustee of the fund. However, the definition is slightly twisted in the event of the death of a member. The subsection provides that the deceased member’s legal personal representative, generally the executor of their estate, may be appointed as a replacement trustee for the deceased member and the fund will still remain an SMSF even though the member/trustee rule has been breached. But, and this is a big but, there is no power or compulsion under section 17 of the SIS Act or otherwise to automatically replace a trustee. The only person who has authority to replace a trustee is the regulator and it is not in the case of a deceased member.

As a result there needs to be consideration of the practical circumstances of how a deceased member’s executor can become a replacement trustee or director and representing the deceased member on the board of trustees. Well here’s the trouble for the lawyers and the advisers to the fund. If the other directors of an SMSF corporate trustee don’t want the executor as a replacement director for the deceased member, the executor, under the Corporations Act 2001, has no power to seek appointment as a director. This is the same with the ordinary trustee rule; if the remaining trustees don’t want the executor as a trustee, well that is the executor’s hard luck. The only way for the deceased to put in place a secure and certain form of action and distribution of their superannuation estate is to hardwire it into the deed.

Importantly, section 17A(3) is an exception to the member/trustee rule, not a prescription or practice of what must take place upon the death of a member. And so it goes on and has been seen in a number of SMSF estate planning cases such as Katz v Grossman [2005] NSWSC 934 and Donovan v Donovan [2009] QSC 26, where the inadequacy of binding death benefit nominations (BDBN) left the trustee or trustees that remain in power with the discretion of how a deceased’s superannuation benefits are to be paid. Even though the deceased and their beneficiaries knew that the deceased wanted their superannuation benefits to be paid to the estate for equal distribution to beneficiaries. I still look back on these cases and wonder why the claimant beneficiary did not sue the accountants and advisers that put the failed BDBN in place under section 55(3) or section 218 of the SIS Act. Maybe next time.

I could go on all day ranting about the importance of the deed and documentation and would still only scratch the surface. For your reference, I have prepared a flowchart on “What Happens on the Death of a Member of the Fund”, a practical guide I teach in my RG146 SMSF Specialist Course. I have left out taxation issues such as the pension transfer balance caps for the deceased’s beneficiaries, investment strategies for any auto-reversionary pension, tax on assets transferred out of the fund and a lot more. This is a practical guide and a useful one to put into play when a client dies. Don’t let things fester and get an action plan up and running. The longer you leave things, the more chance for aggrieved beneficiaries to use their powers to get lawyered up and attack the superannuation estate.

Just to show you some of the issues that can arise as an SMSF adviser when it comes to estate planning, consider the following re-contribution strategy question put to me. And look at the important issue raised around re-contribution on the death of a member considered by the taxation commissioner.

Figure 1: What happens on the death of a member of the fund

Re-contributions into an SMSF for estate planning purposes

Adviser questionIf a 60-plus-year-old client wants to withdraw a lump sum from their fund and re-contribute it back into the fund up to the age of 65 for the purpose of increasing the tax-free component in their accumulation account (to benefit their adult children on death), do you actually have to remove the money from the super fund or can you just do a journal entry debiting a lump sum payment and crediting a non-concessional contribution?

SMSF strategic response

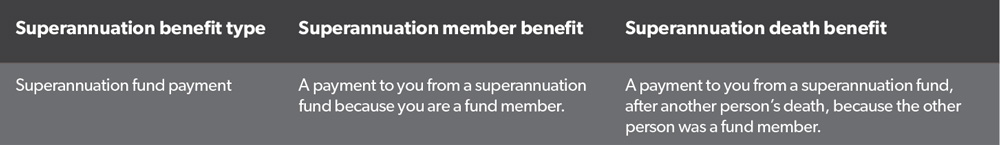

A superannuation benefit is described in section 307-5 of the Income Tax Assessment Act (ITAA) 1997 as per table 1.There are two considerations to this strategy. Firstly, does a journal entry for a payment and subsequent contribution make the strategy work and, secondly, can a re-contribution strategy be used to increase the member’s tax-free component.

In relation to these two issues the commissioner has previously addressed both of them:

Lump sum payments and contributions via journal entry.

Table 1: Superannuation benefits require a payment

Recontributing into superannuation

1. Lump sum payments and contributions via journal entry

In ATO Interpretive Decision ID 2006/132, the commissioner considered the case of the death of a member of the fund and a lump sum death benefit payment, which had been contributed by the spouse back into the fund. The so-called re-contribution strategy. The commissioner held that a journal entry is not a payment under the former section 27A(1) of the ITAA 1936 for the purposes of the definition of eligible termination payment (formerly abbreviated to ETP) and thus the re-contribution was not valid. As can be seen from the table, the current laws in section 307-5 of ITAA 1997 also require a payment to be made to the member of the fund for it to be a superannuation benefit.

The commissioner’s reasoning was as follows: “To meet the definition of an ETP, the majority of the paragraphs of the definition require that a payment be made. It needs to be established whether the journal entries transferring the monies from the deceased member’s account to the taxpayer’s account represent a payment from a superannuation fund for purposes of section 27A(1) of the ITAA 1936. The term ’payment’ is not defined in the ITAA 1936. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the common law meaning of the term.

“The majority of cases that consider whether a journal entry is a payment refer to the principle stated in Re Harmony and Montague Tin & Copper Mining (Spargo’s case) (1873) LR 8 LR Ch App 407. In Spargo’s case it was held that a payment will occur where two parties both have a present liability or legal obligation to the other (mutual liabilities or mutual obligations) and they make an agreement and set off the liabilities against each other using a book entry.

“Based on the principle in Spargo’s case, a journal entry will only constitute a payment if there are mutual liabilities between the taxpayer and the SMSF and there is an agreement between those parties to set-off the liabilities. There is no mutual liability in this case as the taxpayer does not have a liability to the SMSF (Case 18/97).

“Therefore, a journal entry is not sufficient to establish that the SMSF has made a payment to the taxpayer under the provisions of subsection 27A(1) of the ITAA 1936.”

2. Recontributing into superannuation

It has been and continues to be a popular strategy for members of a superannuation fund to withdraw their superannuation benefits and re-contribute this into their superannuation fund. The idea is to take a lump sum out tax-free post age 60 and re-contribute back into the fund as a non-concessional contribution, thereby making it a tax-free component for the purposes of future death benefit payments.

The issue was hotly debated until the commissioner issued a media release on 4 August 2004 – MR 2004/058. In terms of re-contributions specifically, the commissioner stated:

“The tax office today confirmed that commonly-used superannuation strategies will not attract the anti-avoidance provisions in the tax law. Tax commissioner Michael Carmody said he wanted to provide clarity for people on the treatment of a range of superannuation practices.

“We have examined a number of straightforward strategies and confirm that they will not attract the general anti-avoidance provisions.

“Under the law, there is a certain amount of flexibility and choice about when and how people draw on their super savings.”

“The strategies and variations we have examined so far are arrangements to maximise an individual’s retirement benefits and are allowable under law.”

Importantly, if the commissioner is comfortable with the previous re-contribution strategy, which had an immediate tax benefit for the member commencing a pension, one which may or may not increase tax-free benefits to non-dependants only, would appear far too remote for Part IVA of the ITAA. As such, the re-contribution strategy considered is in accordance with the SIS Act and the ITAA and, provided the trust deed allows the strategy, should not breach the anti-avoidance rules.

One aspect to consider in-depth is the withdrawal and re-contribution into a fund that has an accumulation account with a taxable component already. The addition of a tax-free component is a great strategy to increase the percentage of tax-free component for adult dependants. However, a better strategy in this instance would be to have a second super fund that would house solely the tax-free components – the estate planning SMSF. This would ensure a maximum proportion of tax-free component, enabling dependant beneficiaries to take from this latter fund than the first fund muddied with taxable component. Of course, any growth or earnings on the tax-free component in an accumulation account is taxable component – unless in a pension.

New SMSF strategy note: From 1 July 2017, the total superannuation balance (TSB) for a retired member of a fund is $1.6 million. The trustee of a fund cannot accept any more superannuation benefits into the member’s pension account once the TSB is exceeded. This means that in a two-member SMSF, the so-called mum and dad fund, superannuation balances should be equalised in order to maximise a couple’s tax-exempt pension balances. It does not make sense for one of the members to have $2 million in accumulation and building for a pension and the other only $800,000.

In this case the re-contribution strategy above should be used – however, using cash, not journal entries.

Promissory note strategy: In the commissioner’s ruling on contributions, TR2010/1, he discusses the use of a promissory note as being akin to a cash contribution. However, there are certain terms and conditions in relation to the use of a promissory note and you are well advised to discuss this with a specialist SMSF lawyer.