Graeme Colley assesses the potential benefits and drawbacks of the proposal to increase the maximum number of members in an SMSF from four to six.

As announced in the 2018 federal budget, the maximum number of members allowable in an SMSF is likely to rise from four to six people. This announcement proclaimed that the change would expand access to SMSFs and make it easier to roll over existing superannuation funds to an SMSF. The design of the reform is expected next year.

A membership increase may offer benefits for some as it could mean greater flexibility, particularly for small businesses with multiple owners who wish to pool their super into one fund. It could also benefit families and business partners wanting to achieve an intergenerational transfer of assets, especially business property.

With more members there’s likely to be a larger pool of assets in the one fund, instead of amounts spread across many funds. By having all the member’s benefits in just one fund, a greater critical mass is available for investment and may allow the fund to do some things it would not normally do. For example, limited recourse borrowing arrangements are considered more difficult to put in place where there are a number of parties involved in the transaction, but this can be much easier with just one legal owner and one borrower, the SMSF.

Having a fund with closer to six members may provide advantages if the proposals to limit franking credit refunds get closer to becoming reality. A fund with up to six members – some in pension phase, others in accumulation phase and some making taxable contributions – could absorb franking credits by offsetting any excess credits against non-franked income and taxable contributions. That would not be possible with two related SMSFs where one fund was in pension phase only and the other fund was in accumulation phase and receiving taxable contributions at the same time.

It could be possible to reduce the costs of running an SMSF by consolidating members’ benefits from various funds and ending up with a greater number of members. A fund with six members would pay only one ATO lodgement fee, the cost of one audit and one actuarial fee, if required, in addition to many others such as account-keeping fees. There are, of course, the logistical issues if members transfer their balances from one fund to the other. The types of assets being transferred would need to take into account how the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act applied to the transfer and whether it was permitted by the rules that limit the transfer of certain assets between related parties.

"More members may also mean a more decentralised fund with less desirable outcomes. Think of the scenario of children outvoting their parents on investments, estate planning and other fund matters. "

Graeme Colley

The extension of SuperStream to SMSFs will take off one of the difficulties and frustrations in moving members’ benefits from Australian Prudential Regulation Authority-regulated funds to SMSFs. This has been difficult in the past where rollover facilities to enable the transfer have been absent, unnecessarily delaying the flow of benefits between funds. Let’s hope that in future once an SMSF has been established, a tax file number obtained and the like, that the rollover will happen quickly and efficiently to get the fund on the road.

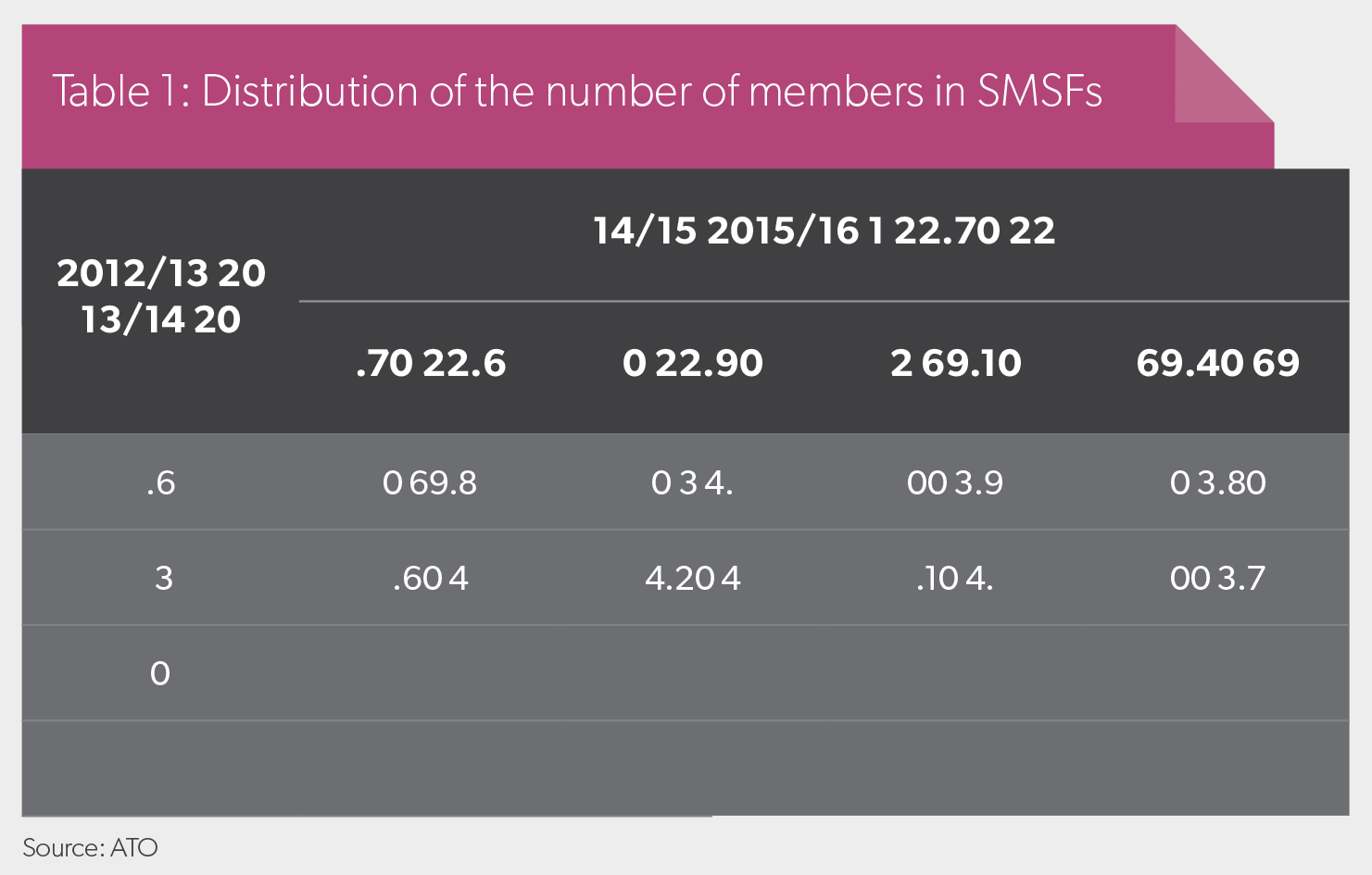

If you look at the existing statistics for SMSFs, the numbers show it all. More than two-thirds of SMSFs have two members, just over 20 per cent have one member and around 7 per cent of funds have three or four members. This suggests a limited underlying appetite for larger-membership funds, and if passed into law, there’s likely to be little impact on the SMSF sector as a whole. The latest available ATO statistics show a very stable population of SMSF members with possible slight decreases in the maximum number for those that have three and four members (see Table 1).

With all the positives created by an increase in the number of members of SMSFs, there are a few things to think through. While there may be a decrease in the costs of running the fund on the one hand, it could lead to increased administrative complexity due to the decision-making process being spread over six members. This could include additional record-keeping, member investment choice, trustee or company director voting rights, or limitations placed by some state trustee legislation on the number of trustees.

When thinking of the costs of running an SMSF, the question of whether the fund is segregated or unsegregated can be an influencing factor. A fund that calculates its tax on a proportional or unsegregated basis may prove less costly as the fund assets are pooled for the actuary to calculate the amount of taxable and exempt income. In contrast, a segregated fund may provide a challenge to allocate investments to determine taxable and tax-exempt income as members are in accumulation and retirement phases.

In some situations, an SMSF may wish to remain segregated, but over time it may end up with a member who has a total super balance that exceeds their cap. This may result in the member having to move their benefit to another fund by selling the fund’s assets or having the SMSF treated as an unsegregated fund, even though the remaining members are under their total superannuation balance cap. Members and trustees of the larger SMSF will need to keep an eye on their total superannuation balances just before the end of each financial year to make sure their cap is not exceeded.

There’ll be the need to make investment decisions for a larger pool of members in the six-member SMSF. And this may lead to a more conventional investment mix than would have otherwise been the case. Recent research involving SuperConcepts and the University of Adelaide has revealed that as the number of fund members increases, investments tend to become less risky, and that groupthink leads towards more familiar assets, such as cash and domestic equities.

A more conservative investment strategy may work for SMSFs that have an older membership base as a more conservative investment strategy may be suitable. However, those funds with basically younger members may need to have a more aggressive strategy to build retirement savings over the longer term. A more conservative strategy may not produce the same results over the same period. So funds wishing to expand their membership will need to take care to properly identify and address behavioural factors such as the preferred investment strategy.

"The main benefit of increasing an SMSF’s membership from four to six members would appear to come from the pooling of assets that would otherwise be spread more thinly."

Graeme Colley

More members may also mean a more decentralised fund with less desirable outcomes. Think of the scenario of children outvoting their parents on investments, estate planning and other fund matters. It may allow them to take control of the distribution of a member’s death benefits in some situations. The voting rights of trustees need to be sorted out from the outset and reviewed regularly as the SMSF changes as members get older or their family situations change. It must be ensured the voting rights of trustees are in line with the superannuation covenants to ensure trustees act in the interests of all members. The outcome could be undesirable and inequitable – not good.

Six members could also result in more frequent membership changes as some members pass on or move to their own SMSF or a publicly offered fund. This could place strain on fund assets, investment strategy, administration and associated costs.

Allowing funds to have up to six members further underlines the importance of appointing a corporate trustee for an SMSF. Under some state and territory legislation there is a limit on the maximum number of trustees of a trust. A fund that has five or six individual trustees under the proposed increase would not satisfy the requirements of that legislation. Allowing a corporate trustee to act as trustee of the fund with the members as company directors would override any difficulties.

Breaches of the superannuation rules are a reality for a few SMSFs and they may be faced with penalties being imposed by the ATO. If a member/director of a corporate trustee has breached the superannuation rules and penalties are to be imposed, the company would be liable once only for the breach. In contrast, individual trustees who breach the rules could each be penalised personally.

The main benefit of increasing an SMSF’s membership from four to six members would appear to come from the pooling of assets that would otherwise be spread more thinly. However, there possibly seems to be a downside relating to the administrative efficiency of the fund, trustee decisions and investment performance.

At the end of the day, when considering the best number of members for an SMSF, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. It will depend on individual circumstances – and a good first step may be to seek advice to weigh up the pros and cons to make an informed decision.