SMSF trustees’ appetite for yield has not waned, but Chris Andrews warns they must acknowledge the level of risk involved and ensure they are properly compensated for it.

It is a common misconception among many SMSF investors that yield-based investment strategies, that is, investing for income rather than capital growth, are inherently low risk. They are not.

There are a range of risks with all of the commonly used yield-based investment strategies. It is critical SMSF advisers educate their clients about these risks and explore all relevant alternatives before finalising their statements of advice.

This article will explore some of the risks inherent in the most common yield investment strategies currently being used by SMSF investors.

The purpose of this article is simple: it is not to argue that any of the common yield strategies are inherently invalid, but instead to argue SMSF investors and advisers need to be aware of the risks attached to each strategy so they can ensure investors are properly compensated for these risks.

Cash and term deposit investments

SMSFs have frequently, and often wrongly, been criticised for overexposure to cash and term deposits. The Australian Taxation Office estimates system-wide exposures of around 28.6 per cent to cash and term deposits as at March 2014, down slightly on the 29.9 per cent reported in March 2012.

While this is higher than what some would consider appropriate for the average investor, it is perhaps not unexpected given the higher balance profile of the average SMSF investor.

SMSF trustees are reliant on their advisers and themselves and broadly make conservative judgments on these matters, which is a good thing. It is, after all, their own money.

The rationale given for genuine cash and term deposit investment, as opposed to temporary holdings of funds awaiting deployment in other investment opportunities, is based on capital security and regular, reliable income streams. Certainly, cash and term deposits served Australian investors well during the period of extreme uncertainty caused by the global financial crisis (GFC), providing confidence and a strong margin for the underlying risk.

From a capital security point of view, cash has long delivered above-inflation returns for Australian investors – especially where the amount deposited is below $250,000 and qualifies for the Financial Claims Scheme, in which the federal government guarantees timely repayment. However, it would be a mistake to regard this investment as absolutely risk free.

Less than 18 months ago it was announced that depositors in the Bank of Cyprus would lose 47.5 per cent of savings exceeding US$132,000. Even more remarkably, former Harvard professor of economics Terry Burnham made headlines earlier this year when he announced he was withdrawing $1 million in deposits from the Bank of America because he was not being properly compensated for risk.

Of course, it almost goes without saying the Australian banking system is currently in far better shape than the systems of Cyprus or the United States. But it would be naive in the extreme to argue there is zero risk of a system-wide crisis that could put Australian deposits at risk. Even the government guarantee could be tested in extreme cases.

As Burnham points out, a depositor in the US also benefits from a government guarantee (to the same amount of $250,000 as applies in Australia) via the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

The risk is that a system-wide crisis could overwhelm the effective ability of the federal government to protect its depositors. That is why it is critical to ensure any cash or term deposit investment generates sufficient yield to compensate for risk – however small you assess the risk to be.

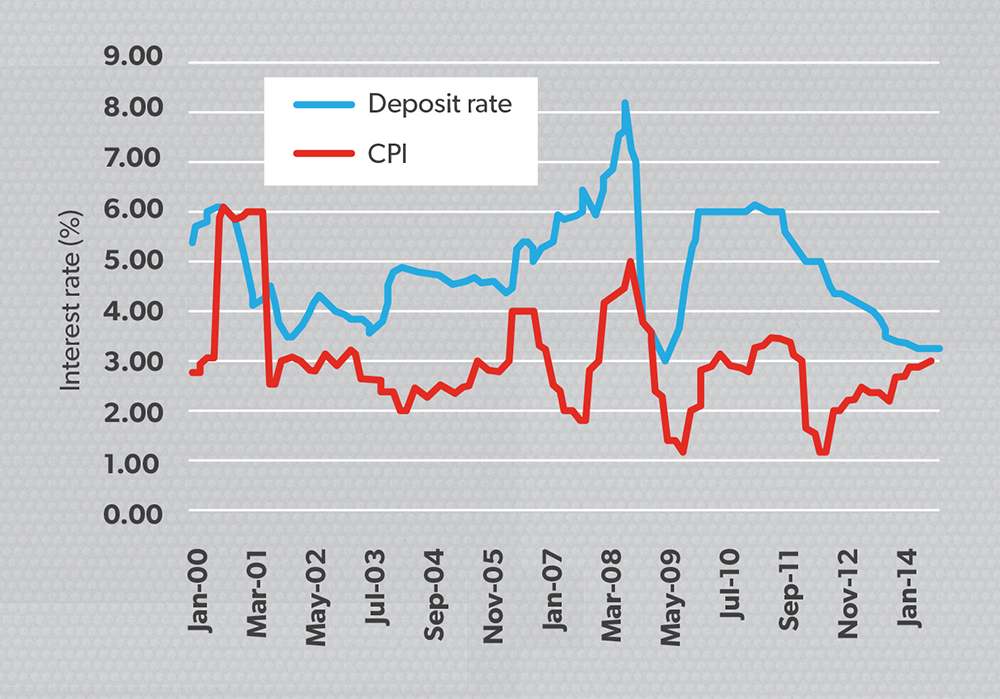

This leads us to consider the second limb of the rationale for cash and term deposit investment, being regular, reliable income streams. As has been widely discussed, the picture here for SMSF investors is not good. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has recently analysed bank deposit rates against the consumer price index (CPI) since 2000 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Bank deposit rate v CPI

Source: RBA

The central bank found the average 12-month deposit rate since 2000 was 4.84 per cent a year. When compared to the average CPI rate of 3 per cent a year, the average real yield on these investments was 1.84 per cent a year.

More recently, outcomes for investors have deteriorated. The RBA found average 12-month deposit rates were just 3.30 per cent a year, with the CPI still sitting at 3 per cent. This has brought the real yield down to 0.30 per cent a year – barely in positive territory. This of course means an investor in cash and term deposits is barely (if at all) retaining the real value of their portfolio.

The ‘nutshell conclusion’ for SMSF investors is that exposures to cash and term deposits have to be weighed and considered very carefully. This is the first time in a while the inflation rate is higher than official cash rates and investors should be adjusting for this reality.

Bonds

The classical yield or fixed interest investment strategy is bonds. Smart investors and advisers are typically well versed in fixed interest products and historically have used bonds well when constructing well-balanced portfolios. As has been widely discussed, bonds have been in a major bull market since the 30-year US Treasury yield hit its all-time high of 15.20 per cent on 29 September 1981. Figure 2 puts things into perspective beautifully.

Figure 2: Interest rates over the past 150 years

Source: Yale University Professor Robert Shiller

Now even bond market stalwarts such as Bill Gross, formerly of PIMCO, the world’s largest bond investor, are calling the end of the bond bull market. Indeed, for about 18 months a range of commentators, including Bank of England director of financial stability Andy Haldane, have been arguing we are experiencing the biggest bond bubble in history.

It should be of particular note to SMSF advisers that even institutional investors are beginning to lock in an adverse view of bond yields going forward.

Asset consultant Frontier Advisors has highlighted low bond rates mean institutional superannuation funds should be questioning whether the advertised likely returns for conservative superannuation options should be downgraded to just CPI plus 1.5 per cent to 2 per cent a year, from CPI plus 2 per cent to 2.5 per cent a year.

It is fair to say anyone who claims to be able to predict exactly how the bond bubble will end is either a genius or deluded. Certainly, a range of powerful national governments and central banks will be trying hard to control it. However, risks abound and SMSF investors should invest in bonds with their eyes wide open to these.

Bank or other hybrid notes

A popular alternative to bond investments in some circles is hybrid notes. These are difficult to assess as a class because their merits are so dependent on the detail of each individual issue.

Broadly, from an investor’s point of view, the ideal hybrid seeks to deliver equity-like returns with something of a fixed interest risk profile. Unfortunately the opposite is all too often true. Investors are exposed to fixed interest returns in compensation for running equity-like risk.

Discerning whether a particular issue is a sound investment is a highly complex analytical task. The standard hybrid offer document typically runs into hundreds of pages and is full of highly technical terms and trigger events.

Frequently – and particularly with the ever-popular bank hybrids – a detailed background understanding of legal and regulatory issues, such as banking capital requirements and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s regulation of these, is required.

The technical scope of individual hybrids may make the time required to understand each simply too onerous for the typical SMSF investor. As Warren Buffett once said: “Investing is not like Olympic diving – you don’t get bonus points for degree of difficulty.”

Equities

A very popular yield strategy with SMSF investors, particularly since about 2011, has been investing in equities for the dividend yield, particularly in Australia with dividend imputation and the tax benefits associated with franked dividends. There is little doubt this strategy has been successful over this period. There have been some very strong dividend yields on offer, often boosted significantly by franking credits.

However, the lack of discussion of the appropriate equity risk premium has been somewhat disconcerting and has been noted by a number of commentators. As we all know, fixed interest investments typically do not deliver returns as high as equity investments, but in exchange investors get greater certainty of return.

Equity investments expose investors to capital risk. The S&P/ASX 200 dropped nearly 50 per cent during the GFC and – seven years later – is still down by about 20 per cent on its pre-GFC high. For SMSF investors who need to sell down portfolios for living expenses this is a very significant capital hit.

Importantly, while fixed interest yields derive from legal obligations (the ‘borrower’ has a legal obligation to make repayments), a dividend is by its very nature discretionary. It might look solid right now, but if circumstances for the company in question change, the dividend is the first thing to be dropped.

To put that in a very contemporary context, Boston Consulting Group (BCG) has just released its “2014 Australian Value Creators Report”. This report highlighted the fact Australian businesses paid out almost twice as much in dividends (as a percentage of earnings) as their global peers in the 2014 financial year.

That difference is staggering and questions must be asked whether this shows that Australian companies are underinvesting in their future. BCG certainly thinks they are and that it presents significant risks to the future return outcomes for investors in those companies.

Underlying capital and income risk is the fundamental equity risk of volatility. Equity markets and individual equities are prone to volatility and – as we’ve already seen – this volatility can result in multi-year or even decade-long periods of underperformance. SMSF investors and advisers must be sure they are properly pricing in this risk in the assessment of any individual equity.

A current darling of the ‘equities-for-income’ strategy is Telstra. But an objective, long-term observation of the Telstra share price reveals a very mixed picture for its investors.

Again, this is not to deny the validity of equity-based yield investment strategies. It is simply to say SMSF investors and advisers should ensure the real risks of this strategy are taken into account.

Conclusion

More and more Australians are taking control of their future through an adviser-guided SMSF. Such individuals are taking a great first step in their security in retirement. Investors and advisers have a range of strategies to consider during both the accumulation (employment phase) and the pension (retirement phase) of their SMSF capital. However, no strategy is foolproof and each has its own profile of benefits and risks.

SMSF investors and advisers need to assess these in detail to ensure their strategy matches the investor’s individual risk profile.

There are many yield-generating alternatives beyond these usual suspects, for example, La Trobe Financial’s capital stable investments that SMSF investors have used for yield. The offerings target a highly diversified, nationwide portfolio of small property credit (mortgage)-based assets.

One investment option has produced a powerful, yield-based return profile for its investors. Its capital stability (zero investor capital losses) and liquidity profile (full capital return on investment maturity) have been coupled with monthly income returns that have been strong both in absolute terms and relative to peers. Just as critically, this return has exhibited the low-volatility profile that so many SMSF investors are targeting.

Given the challenges SMSF investors and advisers are likely to be facing in seeking to secure yield into the future, the alternative may just be worthy of second consideration.