Much of the discussion on fixed income investments centres on sovereign bonds, but, as Elizabeth Moran writes, corporate bonds warrant serious consideration.

The ATO tells us SMSF investors hold around 30 per cent of their portfolio in cash or term deposits. In effect, this is their main defensive investment, offsetting higher-risk property and shares. But with progressive cuts to the cash rate, most deposit rates are under 3 per cent, making it very expensive to retain a 30 per cent allocation to cash. It makes now a good time to consider corporate bonds as an alternative.

The vast majority of corporate bonds are assessed by credit rating agencies and have investment-grade status, making them low-risk, defensive assets. For a slight increase in risk over term deposits, your clients can earn incrementally more by investing in corporate bonds, which can make a big difference to the income of the defensive component of their portfolios.

Bonds are easy once you get the hang of them. Investors lend their funds to a company that agrees to pay them interest on specific dates and return capital at maturity, much like term deposits. Bonds are a legal, contractual obligation and this is important as it means the companies issuing the bonds will do all they can to make sure those interest and capital payments are made. In some cases they’ll take actions shareholders won’t like in order to protect bondholders who have priority in terms of repayment in a wind-up or liquidation scenario. In that regard, it’s important to read bond or debt-specific research as a bond analyst may have a different view of a company compared to an equity analyst.

Three types of bonds

Much of the media conversation around bonds is about United States Treasuries, which are predominantly fixed rate. These bonds are paying very low returns of about 0.50 per cent for three years – not very attractive to SMSFs.

However, the commentators fail to discuss corporate bonds, which pay higher returns and come in three varieties: fixed, floating and inflation-linked.

Each of these bonds offers the best protection in one of three economic scenarios. I’d always suggest having an allocation to all three, but typically you’d weight a client’s portfolio depending on your views of interest rates.

Fixed rate bonds: These are very defensive assets, particularly when interest rates are coming down. The only way these bonds can reflect changes in market expectations of interest rates is through a change in the price of the bond in the secondary market. If interest rates fall, fixed rate bond prices will rise. The opposite is also true: if interest rates rise, fixed rate bond prices will fall. This is why global commentators are concerned about low-yielding US Treasuries and the price falling when US interest rates eventually rise.

Fixed rate bonds pay interest semi-annually.

Floating rate notes (FRN): These are securities that pay interest or a coupon linked to a variable benchmark. In Australia, most FRNs pay a coupon set at a margin above the bank bill swap rate (BBSW).

Interest is paid quarterly and determined at the start of the period by applying the margin to the benchmark on the first day of the three-month period. The BBSW will rise and fall over time based on prevailing interest rates. The margin over and above the relevant benchmark is usually fixed and will be set at the time of issue. FRNs, because of the way they are structured, typically protect a portfolio when interest rates are rising. That is, as the Reserve Bank of Australia increases the cash rate to try to slow growth in the economy, FRN interest payments will also increase to reflect market expectations of higher interest rates. Typically FRNs outperform fixed rate investments, such as term deposits and fixed rate bonds, under these economic conditions.

Inflation-linked bonds: These offerings are the only 100 per cent hedge against inflation. If you have investors new to bonds, inflation-linked bonds are a good place to start. They pay a fixed margin over the consumer price index (CPI).

Most older investors will remember when inflation was over 10 per cent a year in the 1970s and 1980s. While it’s been relatively benign in recent years, massive quantitative easing means inflation could spiral in the future. These bonds are typically long dated and issued by infrastructure companies with monopolistic characteristics.

Both inflation-linked bonds and FRNs pay interest quarterly.

Portfolio comparison

To illustrate the difference a corporate bond portfolio can make to your clients’ income, we’ll look at a simple example. Assume a client has a $1 million portfolio split evenly between term deposits and shares. A good one-year term deposit rate is 3 per cent. So income on $500,000 at 3 per cent is $15,000. The shares are expected to earn more and for the sake of simplicity let’s assume they earn 7 per cent, including franking. Income on the shares is then $35,000, providing total income on this portfolio of $50,000. If we change the mix to add bonds, the portfolio allocation becomes term deposits 10 per cent and bonds 40 per cent, with shares remaining the same at 50 per cent. The term deposit of $100,000 will earn $3000. The 40 per cent allocation to bonds is projected to earn income next year of 4.90 per cent or $19,341. Of course, depending on what happens to the CPI and BBSW benchmarks, the FRNs and inflation-linked bonds may earn more or less income, although forward projections on the BBSW are already included. The contribution from the shares remains the same at $35,000. Income on this portfolio next year is therefore projected to be $57,341 or $7341 more than the first portfolio.

All up, income is up by 14 per cent over the first portfolio.

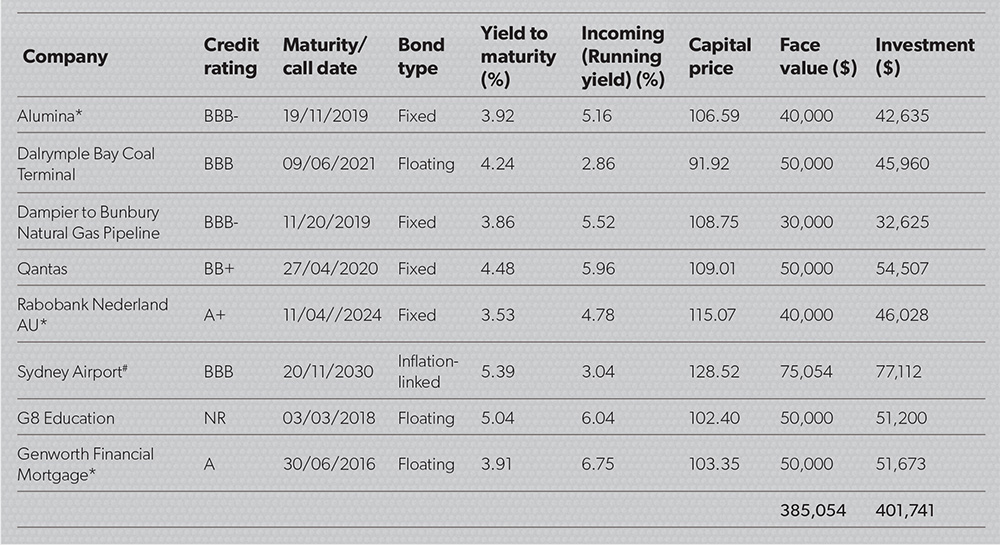

Table 1 shows the bond portfolio, which consists of eight companies. Most are investment grade, with a credit rating of BBB- and above, the two exceptions being Qantas and non-rated Australian Securities Exchange (ASX)-listed childcare provider, G8 Education. Overall returns are boosted by including allocations to these two companies. Conversely, the Rabobank bond has the highest credit rating, implying it is the lowest risk, but also note it has the lowest yield to maturity of 3.53 per cent, still relatively high in this environment, which provides compensation for the longer term to maturity of 2024. If your clients wanted higher returns, you could reduce or remove the Rabobank bond from the portfolio and invest in other higher-risk bonds. The reverse is also true. If clients wanted a lower-risk portfolio, Qantas and G8 Education could be replaced with lower-risk bonds, although this would reduce expected returns.

Table 1

The portfolio has a mix of bonds, with a 44 per cent allocation to fixed, 37 per cent to floating and 19 per cent to inflation-linked. I have a general view that interest rates will be lower for a long time, so I am happy to invest in longer-dated fixed rate bonds, but your view may be different and you may want to adjust the allocations.

The column marked ‘Yield to maturity’ lists the expected return if you hold that bond until it is due to be repaid. If you acquired this portfolio and held it to maturity, the total return is expected to be 4.41 per cent. The ‘Income or running yield’ column provides your expected income in the next 12 months from each bond. Income for the portfolio for the next 12 months is forecast at 4.90 per cent.

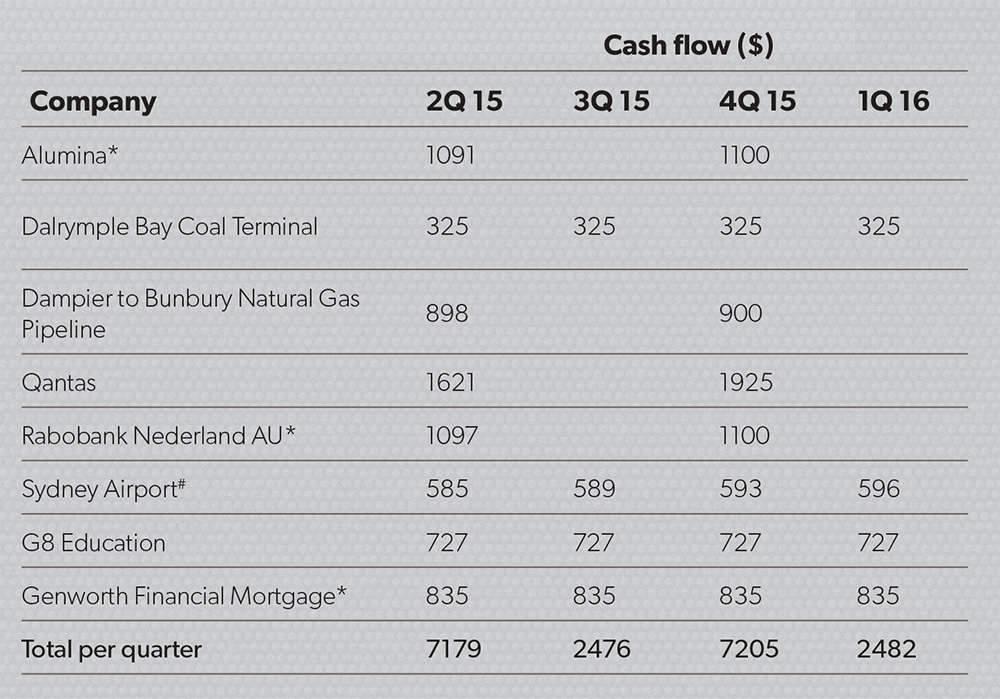

The cash flows of the portfolio are much more regular than term deposits that typically pay annually, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

How to buy bonds

Many investors access bonds through managed funds. While they provide great diversification, few disclose the full range of investments, so in that regard they lack transparency. They also sit behind a unit price and the manager decides when to pay income, so they fail to offer the same benefits of direct investment where income is predictable and you get your funds back at maturity.

Fund managers, like other bond investors, generally source bonds through the over-the-counter OTC market. The market works much the same as the foreign currency market, with a bid/offer spread, where the brokers make brokerage on the trade. Only a small handful of bonds are available through the ASX.

The bonds mentioned in this article are only available in the OTC market where minimum transactions are generally $500,000. Some brokers, such as FIIG, make bonds available from $10,000 per bond with a minimum upfront spend of $50,000.

The benefits of corporate bonds

Corporate bonds are low risk and provide a defined income stream and capital stability.

Bonds are great diversifiers. They give investors other defensive options besides cash. They are also issued by companies not listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), including big foreign companies that issue in Australian dollars, such as Swiss insurer Swiss Re and United States investment bank Morgan Stanley. Australian companies also issue bonds in foreign currencies. These are great for investors that hold funds in overseas bank accounts earning very low returns.

Bonds rank higher in the company structure than shares. If a company goes into wind-up, bondholders will usually be repaid before any funds can be returned to shareholders.

Inflation-linked bonds are the only 100 per cent direct hedge against inflation.

Bonds are generally liquid investments, and while some have very long terms to maturity, there is an active secondary market. Investors do not have to hold investments until maturity.

There is an opportunity for capital gain or loss if you sell prior to maturity, but your return will be positive if the bond is held until maturity.

Risks

Any investment has risks. There are three main risks with bonds.

Interest rate risk – the risk associated with an interest-bearing asset, such as a loan or a bond, due to variability of interest rates. This predominantly affects fixed rate bonds.

Credit risk – the risk that the issuer may be unable to meet the interest and/or principal repayments when due, and thus default on the loan. Generally, the higher the credit risk of the issuer, the higher the interest rate that investors expect in return.

Liquidity – the risk that a security cannot be easily sold at, or close to, its market value. Generally bonds are fairly liquid, although in stressed markets they can become less liquid.